"Rest of the World 2013-14" story # 48

SECOND EFFORT

Kibish, Ethiopia

July 28, 2014

The Disi people’s town of Tum, where I camped two nights beside friendly soldiers and met a beautiful local family, bordered the Surma region.

The soldiers found me a ride in the back of an Isuzu truck. We descended from the highlands of the Disi people to the lowlands of the Suri. I loved the land in this part of Ethiopia; fields of short rice grass, dotted with trees too strong to be chopped down, appeared in the hills. Otherwise, everything was tall grass – dry enough to walk through, thick enough to conceal mysteries. Dangers. The two policemen who also rode in the back of the truck cocked their guns, in preparation for our entrance into the Surma region.

We came to some Suri people walking in the road. They wore nothing but purple or green cloths. They carried only guns. “Tselli!” I greeted them happily.

Since leaving the Surma region three weeks earlier, I’d plotted to return. But, I needed to resolve one problem: I needed a safe, free place where I could stay. I only had $140 for my remaining month and a half in this country. Of course, I couldn’t contact any of my Suri friends, because phones didn’t work in their region. I could only go there, as I was doing. Hopeful that someone, anyone, would invite me to stay with them.

The truck stopped in the Suri’s first town. Koka. I walked to the place where I’d previously camped in another soldiers’ post. Instead of soldiers, I found Suri policemen. They told me to sit down, and I waited for another ride. They drank something from the large half of a gourd. It was an earthy brown, dirty drink called “gesu”. They said it was food, and they offered me some.

Earthy, tasty, and sweet. A bit like egg nog. My head swam, and I recognized the “gesu” was alcoholic. They said it was made from corn and small, fuzzy berries (sorghum). They drank the rest, lay down, and began begging me for everything they saw. My knife, my sweatshirt, my hat.

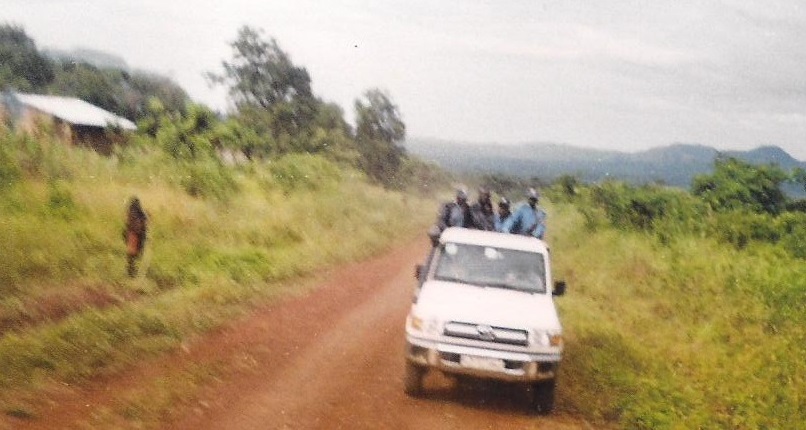

A pick-up truck arrived that could take me to my destination. The village of Tulgit.

In fact, I probably wouldn’t have returned to the Suri … but, the rest of Ethiopia usually made me feel bad. The people thought about money so much that even their jokes were related to money. They’d become ugly and personality-less. People called to me on the streets, endlessly, and yet if I responded to their calls only 1% of them were offering friendship. It was difficult for me to spend five days in Ethiopia, let alone forty-five.

But, Surma was different. As I sat on my bag holding onto the back of the pick-up truck, climbing up the tall grass mountain of Tulgit, I thought to myself: Was I going to find freedom here?

“It’s worth facing many difficulties to achieve freedom.” – J.Breen philosophy

In Tulgit, I was quickly recognized by a boy named Bar Lusa. I’d once given him a free English lesson. He was one of three Suri who I thought might welcome me to live with his family. And he did so. Immediately. “You can eat Suri food,” said the small-headed, sympathetic boy. Wow. I was so happy!

He led me through the tall grass, and we came to huts which I never would’ve guessed were there. One of them was his. He helped me set up my tent in a corner of the clearing. We were joined by a beautiful young girl with her beautiful young breast showing; she had soft eyes and lips, and clay discs with white swirls in the bottoms of her ears.

Bar Lusa’s young brother, Bar Solomon, appeared. He and his friend were playing and had painted white clay masks on their faces. Bar Lusa’s mother came and seemed welcoming. Wow! This was so great.

Meanwhile …

The truck I’d ridden in was parked at the mechanic’s shop in Tulgit; it was destined for Kibish, the regional capital. I would learn that the Ethiopian driver of this truck worked for the “Peace Police”. He drove dangerously quickly, seemed arrogant, and rolled his shirt up to his chest so that his ass-crack was visible. Two Suri policemen had been riding in the back of the truck.

Suddenly, one of those policemen peaked through the tall grass surrounding Bar Lusa’s home. Stretched ear-lobes hung from his dark and thin head. His red eyes burnt with anger as he glared at me.

What was this? Did he want me to pay him as a police escort for accompanying me during the ride?

It wasn’t clear what he wanted. But, he forced me to take down my tent. He was mad at me for disappearing into what he called “chaka” (the forest), and said it was dangerous. He ordered me to go with them to Kibish, so the regional police could learn about what I was doing here.

Wow. What an abrupt change of luck!

I did not want to go to Kibish.

People had told me bad things about it. I also knew that the regional authorities sometimes charged tourists $20 a day, just to be here.

I protested. I stalled. I hoped the policeman would get tired and leave. But, he persisted. I told him I would leave the region immediately, I would turn around and hitchhike elsewhere. But the man, a chief of police, wanted me to go to Kibish.

We walked towards the truck.

MODERN ODDYSEUS’ TIP FOR POLICE EVASION – When you’re going to run from the police, don’t let them know you’re going to run until the last possible second.

Walking quickly, I veered away from the truck. If I could’ve walked to the end of the region without them catching me, I would’ve. But, that was impossible. My only move was to seek refuge in the home of the Ethiopian preacher, Dr. Haile.

I walked quickly in that direction.

There were now a total of three policemen present. They yelled after me, chased me, ran to intercept me. They didn’t shoot their AK-47s nor hit me. They grabbed me by the bags I carried. I shed my jacket, bags, and water bottle, like a chameleon sheds its tail. The only thing I went back for was my Detroit Tigers’ baseball hat, which got caught on a branch.

The door to Dr. Haile’s home was open. But, would I make it?

Somehow, I made it inside. I sat down beside Dr. Haile’s table, where he and his wife were having lunch.

And all was clam.

Asylum.

The police, respecting the doctor, remained outside the door. A crowd of spectators gathered behind them.

The doctor and his wife stopped eating their lunch.

Catching my breath, I told the doctor what the police wanted me to do. He and I had previously developed a rapport, because he’d done his veterinary studies in Moscow and spoke Russian. He advised me, “The ‘woreda’ (region) wants to know what you’re doing here.”

I said, “That’s good for them. It’s not good for me!”

I continued to sit. I wished the driver of the truck would grow impatient and leave. But, he continued to stand outside the door. Was it he who had ordered the police chief to detain me?

“You know …” said the doctor calmly, ”this is bad for Mr. John.” Mr. John, the missionary from Kansas, was currently away from Tulgit.

Only after a long while – which I considered admirable of the doctor – he said, “This is also bad for me.

“Please go.”

I knew there was no other choice. Expressing my fears, I had the doctor translate the following questions:

Were the police going to beat me? Surround me and interrogate me? Torture me? Were they going to restrain me, or could I walk to the truck freely?

Their answers: No. No. No. And I could walk to the truck freely.

“Okay, I’ll go.” I asked the doctor’s wife for a glass of water.

Then, I threw it in the police chief’s face and ran out the door!

... just kidding.

I bowed my head and walked to the truck, where I found all of my possessions. I shook Bar Lusa’s hand, good-bye. As my truck drove away, some Suri boys showed me solidarity by pounding their hearts with their fists.

We drove up and over a mountain. And into the low Kibish Valley ...

If it was the police’s intention to try to get money out of me, they must’ve realized I was poor before they could execute their plan. They never asked me for a penny.

They casually asked me two or three questions. A Commander Wodacho took my Michigan drivers’ licence as a document. He said I would probably be expelled from the Surma region. He would let me know in a day or two. For the meantime, I could set up my tent somewhere in the police enclosure. I was free to do whatever I wanted, in Kibish.

A “day or two” became three, five, a week and more. The police forgot about me. Commander Wodacho left town. Nobody knew where my drivers’ licence was.

I was happy. Every day I spent in the Surma region was a success.

In many ways, Kibish was a horrible horrible place. One or two hundred highlander Ethiopians lived here, for permanent business or temporary civil duty. Nearly all of them hated Suri culture.

The Suri culture in this town was pretty despicable. They came to town in their traditional clothes, from huts concealed by the valley’s tall grass. Sitting or standing around, nearly all of them begged. They reached for my pockets. They wanted money so they could get drunk. One day, I sat outside a dark room where Suri people sat and drank “gesu” sold to them by a fat Oromo woman. I watched a girl with a baby, as her fingers played with the extended lower lip that hung from her mouth like a beard; her eyes contemplated life with the confusion of youth mixed with alcohol.

But, I always forgave the Suri. I loved them, they were generally quite happy. I communicated in their language and found people who didn’t beg. Their culture was remote; it was the highlander Ethiopians who became my real friends in town. But every day, I had an experience that brought me closer to the Suri.

And I couldn’t help but be attracted to their beautiful women.

“Beauty is the wonder of wonders. It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances.” – an Oscar Wilde character

One day, I met a tall woman in a purple cloth. She carried cabbage on her head, and a nursing baby on her hip. She joked that I should take her baby to America, and I pretended to take it. She had a small broad nose, large eyes, full lips left unaltered, and a soft round breast visible. Her name was Nga Bume.

Another time, I was greeted by one of three girls transporting grass on their heads. I could only see her soft dark jaw and shapely sculpted boob. I ducked to see her eyes through the grass, and we laughed. She was Nga Sede. She delivered the grass. And then she took me by the hand and led me for a while until she disappeared, towards her home or to gather more grass.

But if I was going to know this culture well, I needed to learn its language:

Surichen.

the Modern Oddyseus

Thanks to Bar Bri; a road construction truck; and Addisu for good rides!