"Rest of the World 2013-14" story # 47

FURTHER WANDERINGS OF THE MODERN O.

Tum, Ethiopia

July 22, 2014

Nine days after dancing shoulder dances in the Ethiopian city of Mizan Teferi, I found myself once again in this country’s Surma region. I stood on the one sand street of the town of Kibish - the capital of the Surma region, the most remote place I’d been in this country. Rusted tin roofs of shops and government offices rose alongside the street. Kibish’s low valley was encircled by mountains green with tall grass. Some of these mountains had broad and flat tops, some had sharp tops, some were shaped like stalking leopards.

In this wild frontier town of alcohol, guns, and beggars, I stood beside two policemen and a highlander Ethiopian. I, unlike them, was able to hold basic conversations in the Surma people’s language – a nasally language of “nyuh” and “nguh” sounds which seemed typically African.

Thin, dark Surma men walked around in Western t-shirts or dark green cloths. The Suri women preferred their cloths.

An old, drunk woman begged from me. I could see one of her saggy, shriveled boobs; and her dry, extended lip hanging down from her dry, bald head.

I was able to have a conversation, over her shoulder, with a tall and thin and dark boy with a small and sympathetic head.

“Sara gunyu keli eneng?” I asked the boy in the purple cloth. (What’s your name?)

“Sara ganyo keli Delka.” (My name is Delka.)

“Delka? Sara gunyu a challi! Suri zugo a challi.” (Delka? That’s a very nice name! Surma people are very good.)

We asked each other ten or twelve questions, before I ran out of vocabulary. I enjoyed conversing with the Suri people so much that these conversations alone made me happy I’d come to Ethiopia.

But, how had I gotten to Kibish from the city of Mizan?

The answer to that question was a story of its own ...

My friend Girma Tizazu had invited me to visit his farm. He drove me out of rainy Mizan Teferi. He drove us in the direction of the Suri people, but on a different road than the one I’d traveled before.

The high road:

Dark grass. Dark huts. Dark rain and clouds. Dark, round-faced Benche and Menet people wearing bright Western clothes. Few cars. Little money.

Girma Tizazu was an Ethiopian who’d spent fifteen years in Australia. Now, he was back in his home country, investing in remote farmland. He’d given me a ride during my second week in Ethiopia. And we’d had a good conversation. Now, I was meeting his co-investor, Barakain Tizazu. Girma’s brother, this man was the artistic director for Circus Ethiopia – a dance/acrobatics group that performed internationally and nationally. Once, the Red Cross sponsored them, and they made a show with tight-rope walkers to illustrate the danger of landmines.

The two brothers had cleared a rice field in the jungle. A narrow and muddy river ran beneath it. Swimming, I let the river carry me through the jungle to a place where noisy monkeys were playing. I wanted to swim with them, but they scattered when I approached. Maybe they thought I was a crocodile?

The farm manager said, crocodiles lived in a bigger river ten kilometers away.

This humble man, Binyam, knew a lot about southern Ethiopia.

He said the local people, the Menet, didn’t consider themselves beautiful until they’d knocked out their two front incisors with a piece of wood. They carried guns, but Binyam said they were friendly and very kind. They were vengeful, though, and if the Suri – for example – stole one of their cows, they might steal ten in return.

Binyam told me about the Guji tribe, from another part of southern Ethiopia. Traditionally, their young men must kill someone and cut of his genitals and bring them to the girl he wanted to marry. This proved that he was a man.

That was somewhat similar to “donga” stick-fighting. This tradition of the Suri’s required two men to do battle with tip-less spears. (I’d often seen Suri men practicing this sport, swinging their sticks through the air at head-level.) “Donga” wasn’t meant to be fatal. But, the young winner got to marry his girlfriend. He needed to find enough cows to pay for her, though, and sometimes he decided to steal them.

Binyam talked about these things. And he also gave his opinion on malaria.

He said, if he had malaria in his blood but he ate well, he wouldn’t get sick.

I agreed with him.

In 2012 in Guinea-Bissau, I’d been diagnosed with “a little bit of malaria” in my blood – four times. It was the rainy season. My symptoms included a foggy head-ache, and a nearly constant feeling that I was too hot. Afterwards, I would meet a Danish doctor who said Guinea-Bissau’s hospitals diagnosed nearly everyone with malaria and gave them malaria medicine, just to be safe.

In 2014 in Ethiopia, I also got head-aches. I changed clothes often, trying to find the right combination that wouldn’t make me too hot – or too cold, following a long rain.

I drank up to ten liters of water a day. I ate five times a day: peanut butter, bread, samosas full of lentils, avocados, bananas, meals with injera. My food had never tasted so delicious, nor made me feel so good. I took my time, and walked slowly.

The rainy season was tough. I didn’t know what malaria was, or if I’d ever had it. But, I believed it was important to meet the special needs of my body here. If not, I was going to be in trouble.

The Tizazu brothers treated me to shredded bits of meat. Crisp, thin injera bread. Salty cabbage from their farm. I ate the most, just ahead of Binyam.

The Tizazu brothers returned to their families. To modern civilization. I followed the high road ... towards the Surma tribe.

I became side-tracked by the promise of a nearby, very remote national park full of animals. Wait. How could a place that was nearby be remote? Oh, yeah. I was already remote.

But, Mui National Park beside the Omo River was so remote that there weren’t any cars going there. I could’ve waited weeks for a ride – in the dark land and cold air of Maji. And the local police kept ordering me to waste my time by doing illogical things. They wouldn’t let me walk to the next town, because the Disi people were fighting Surma people in the roadside forest.

I turned back from the town of Maji. I traveled through a vast landscape of surrounding green mountains. I came to Tum, at the foot of green table mountains.

Soldiers were stationed here. They welcomed me and fed me, with a warm hospitality that all Ethiopian soldiers must’ve shared. I befriended Addis, a happy guy whose name meant: “new”. (Elsewhere, I’d met a girl named Ababa whose name meant: “flower”.)

I left my home with the soldiers and wandered around. The town of Tum was home to the Disi people: shorter, round-faced, mountain-dwelling people who often fought with the Suri. Actually, almost everyone fought with the Suri. I hoped the Surma people were going to forgive me for befriending their enemies!

A fourteen-year-old girl called me to her hut in the forest.

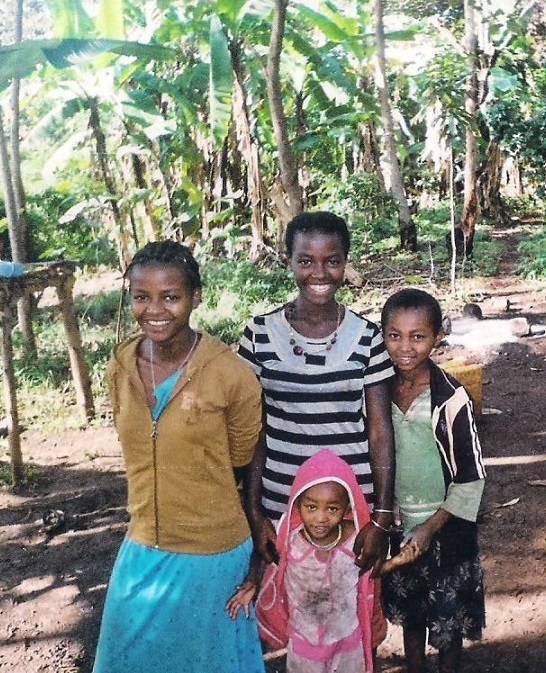

The front wall of the hut was fully decorated with kids’ handprints, made from white or black clay. Following the girl to the back of the hut, I found many children. They wore shabby Western clothes. Cute kids had short, stubby hair and big eyes; were they girls or boys? Girls.

In the hut’s backyard, I found three beautiful women. It was like stepping into a dream.

They wore long, light-weight dresses. A thin, dark-skinned woman wore blue. A thin, light-skinned girl wore pinkish white, and her smile twinkled beneath tiny braids that hung off her head like worms. The third young woman wore an orange dress, and an orange cloth wrapped around her forehead. This petite, dark-skinned girl was named Yimungshal. She had a smile so bright it could’ve brought peace to the world.

They told me to sit down. Sheets of sunlight made their way through the hovering canopy of large, floppy banana leaves to kiss the bare earth.

Yimungshal and the woman in blue kneeled on the ground. Their upper bodies pulsated like machines, as they mashed maize between their hands and smooth stones. The corn mash oozed off of the stones, onto flattened banana leaves. The girl in pink then wrapped this corn mash in maize leaves, shaped it like a pie, and cooked it in a pot.

I was happy to be here and to talk to them in Amharic.

They were all so happy. They said their family was made up of a father, a mother, eight sisters. And a brother: the broad-smiling, dark-faced boy named Amaneli. The sisters’ names included Yordanos, Masalech, Darartu, and Tifelik.

Over the next full day, I would visit them several times. They gave me boiled corn and spicy coffee.

Mostly, I spent time with Yimungshal. She felt the softness of my hands and the hair on my arms. She put a braid in my hair. Her neighbors called me her husband, and she smiled. I might’ve smiled, too. But, I knew she was too young for me.

And so, I resumed my plan to revisit the Surma tribe.

But, how would I get all the way from Mizan to Kibish?

The answer to that question, it seemed, was going to require a second story.

until then,

the Modern Oddyseus

Thanks to Andrees & Freon; an Isuzu truck; Sambad, Solomon, Girma, & two policemen; and Esmeralda Jibri Selasie for rides!