"Rest of the World 2013-14" story # 33

SAHARA

Ksar Ghilane, Tunisia

March 12, 2014

My travels in the Sahara Desert continued.

Hitchhiking out of Tozeur, I got a ride in a semi-truck that carried me for an hour across the Chott Djerid. This gigantic basin, which was sometimes full of salty water, was now little more than a dried-out pit of sand. My driver said, it was dry because there hadn't been much rain this year. I wondered how often it filled up. Every year? Every ten years? I saw a donkey sculpted out of salt in the basin, and I realized this great expanse would've been a great place to walk around with a pack animal.

I continued hitchhiking, and spent the night near the city of Douz. I camped among sand dunes, and the sand made my body cold at night.

The next day, I got picked up by three men who were going deeeep into the Sahara Desert. I searched my map for the small road they'd be taking, and their destination which wasn't marked with the dot of a town but by a blue "yin-yang" sign representing water. Water in the desert. To my great surprise, my drivers were transporting sheep there. I wanted to go to this remote desert outpost, where sheep vacationed during spring! My drivers - a young man named Khalil, and two middle-aged men named Mohammed and Abdul-Hamed - welcomed me along for the trip.

Turbans were wrapped around the heads of the older men. Mohammed sat in front, and was serious with thoughts of business. Abdul-Hamed sat next to me in back, with a dark and deeply wrinkled face. He liked to laugh. His smile revealed the pearly white teeth of a child, and clear chocolate eyes that contained 24-karat gold.

It was a sunny day, but a chilly wind entered our truck and forced me to put on and take off my scarf a dozen times. I wished I had a turban. Young Khalil drove us and, like me, was happy to be going to a new place for the first time. The sheep, which were going to graze in the desert for a few months, may have belonged to Khalil's dad - Mohammed.

I didn't care who the sheep belonged to. This trip of ours seemed unreal, and the place we were going to - unreachable. But, we did reach it. This came after one hour on an empty road, one hour on an even smaller road, and after passing nothing but three cafes, an oil refinery plant, and a prison. We reached Ksar Ghilane.

I wasn't exactly sure what a "ksar" was. From pictures I'd seen, they seemed to be a type of desert architecture in which long three-story buildings were made of rooms shaped like rounded coffins. Each coffin had a door that was always open, and the second- and third-story doors led to small ledges which the inhabitants could stand on or fall off of. The ksars were the soft brown of clay, except for their painted white ledges and rounded tops. I wondered: Did entire communities live together in one ksar? Did they sleep standing up in their coffins?

Ksar Ghilane wasn't like the pictures I'd seen.

Its one-story buildings were made up of five coffins each. They'd been made out of gray concrete, rather than Saharan clay. In the settlement of Ksar Ghilane, there were enough of these buildings for about sixty people.

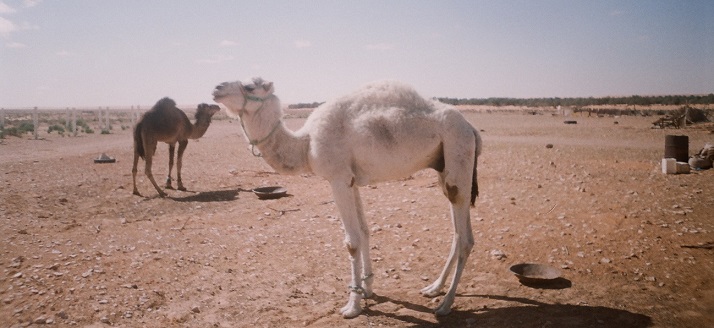

Camels stood around with their hooves tied together, looking at me with their lips tucked into their gums. Donkeys sat in the sun. Chickens wandered about. Goats and sheep crowded together in shelters made of sticks. What were some of these animals doing here?

Sulfurous, stinking water spouted from fountains and faucets. Elsewhere, a hose and pump brought delicious water to Ksar Ghilane (from a hundred meters below the desert, according to Khalil). Near the settlement, a short but dense line of palms and other trees grew. I wanted to explore those trees. But, my ride was leaving ...

Ksar Ghilane was surrounded by humps of swirling orange sand, with green stick-like plants presenting small purple flowers. My ride and I had eighteen more kilometers to go. We left the paved roads behind and drove straight through the desert.

We drove to a flat, stony expanse. Small mountains or dunes rose in the distance. We came to a single, dark-skinned shepherd who wore a white turban and carried a staff in each hand. Hundreds of sheep were scattered around him. No grass could be seen. Two shacks stood, seemingly made of the orange sand and gray stones that made up this Saharan plain.

I was amazed by this place, by this shepherd's job.

I helped my drivers lower their ten sheep and four brown goats from the back of their truck. I ran to round them up, when they began to wander.

The shepherd, the sheep, and our truck advanced one kilometer. We found dry green plants called "ghezzir". Baby goats stood on humps of orange sand, pulling at the ghezzir. One man and I began collecting these plants, to make a large fire. Khalil and Mohammed mixed flour with water, and cut up vegetables in a pot.

Our large fire blazed. And then it died. Khalil sculpted his dough together to make what could've been a very large pizza. He buried this in the sand and ashes where the fire had been. After ten minutes, the baked dough had a dark and crunchy taste - except for the burnt sticks stuck to it, which tasted like ashes. I liked this "mela", a.k.a. Bread of the Sand.

Mohammed brought us a bubbling pot of red stew, called "merga". I dipped some "mela" into it, and tasted a combination of peppers, spices, tomatoes, and Ksar Ghilane's delicious water. One of the best tastes I'd ever experienced. I ate from the merga's rubbery sheep meat and potatoes and slimy peppers and tomatoes and carrots. I didn't want this meal to end.

But it did, and so did our trip to the desert. We drove back towards Ksar Ghilane. We passed another small forest of trees, which must've contained water for the shepherd and sheep. We met a boy who was walking with three donkeys from this forest - to his home, somewhere in the desert.

I would also spend this night in the desert. But, I would be closer to civilization, beside an empty "main" road.

The night sky was clear. Above my tent, Orion the Hunter grew to be huge. And he was surrounded by a circle of stars.

I awoke in the morning and was near to my next destination ...

Empty and lifeless, brown rock rolled and rumbled around to form the Matmata Mountain Range. The bare mountains were interrupted by the exploding green of palm trees.

My drivers and I came to the village of Tamezret.

Crumbly homes with jagged pointy steeples were stacked on top of each other atop a mountain, like a bunched-up fighting pyramid. The homes were a chalky brown, intermixed with a few chalky white buildings. Here, my drivers and I drank green tea with floating almonds. They said, Tamezret was mostly abandoned.

We drove on through the mountains, and saw a "ksar" museum like the ksars I'd seen pictures of. Hmm ... cool! We passed a chalky white mosque with a jagged minaret. All alone in the naked rolling mountains, it was the most beautiful mosque I'd ever seen.

The road led us to the tops of cliffs. From here, we looked down on the town of Tajnoune.

Far below us, the browns and earthy whites of rectangular stony homes wiggled around each other in a rocktop orgy. Tajnoune was a part of the mountains, in the way an ant farm was a part of the earth. I could see circular depressions interrupting the town; were those the famous "Matmata homes", built into subterranean caves?

We drove down to this remarkable town. The most beautiful carpets, mostly red and occasionally blue, were hung to be sold. Berber drawings of arrows, diamonds, and camels decorated them.

This dying town owed its current economy to tourism. The Tunisian man I rode with, Kader, wondered: How had Tajnoune's inhabitants survived here before?

The other person in our car was Nicole, an adventurous retiree from Belgium. She drove me and Kader straight through the Matmata Mountains, to the sea, onto a causeway built long ago by the Romans, and to my final destination in southern Tunisia. The island of Jerba.

Square, bright white architecture wore roofs like spherical bubbles. On small houses and large mosques, white moons dominated the towns. Doors and windows came in turquoise, olive, sky blue, and lime.

Beside the doors were paintings of blue-outlined fish, "hands of Fatima" which brought good fortune, and green lotus flowers. Jerba was, after all, the site of Homer's "Land of the Lotus Eaters". Red, yellow, and magenta flowers clung to the white walls of quiet alleys. Above me, the rooftop terraces took advantage of Jerba's sunny weather.

In an old medina, I walked down an alley through a series of arches. I came to a hidden plaza with clay pots built into the walls. I entered a "caravanserai" market building, and stood in its central opening; two floors of arches encircled me, and I felt like a camel being examined by desert merchants.

Boys in kippa hats ran from synagogues and disappeared in medina labyrinths; fat men in kippa hats wobbled down pedestrian streets. At least fifty Jewish families still lived on Jerba.

....

Nicole from Belgium had a home on this island. And she let me stay with her a few nights. By day, she and I ate fish on the beach.

By night, I put on my kashabiya. I asked Kader, "Don't you have a kashabiya?"

He said, "No. I'm not old yet."

Was he implying that only old people wore kashabiyas? Hmm ... now that I thought about it, I'd only ever seen one man younger than me wearing a kashabiya. I'd seen lots of older men.

Oh, no. My kashabiya fashion had been insulted!

It was time to go home.

It was time to return to Sminja.

The Modern O.

Thanks to Mohammed; Taher; Amur; Adi, Ali, Mouad, & Amir; Khalil ben Mohammed, Mohammed, & Abdul-Hamed; Nicole & Kader; Bechir Misaoud; Kamel; Sebastien & Cyril; Fethi; Alexander & Anastasie; Murad; Mohammed; and Dr. Ben Brahim Ali for rides!

Much thanks to Nicole for the place to sleep!