"Rest of the World 2013-14" story # 32

THE "OASIS" CONCLUSION

Tozeur, Tunisia

March 8, 2014

"Are you a Muslim?"

Tunisia's national guard was detaining me for the second time in three days, and I sat inside their office building. They had some questions for me.

"No," I answered the first.

"Did you go to the mosque this morning?"

These guys must've been gathering information on me. "No." I corrected them. "I went to a mosque last night. But, I didn't pray."

Hmmm. A guy who goes to the mosque but says he doesn't pray? That was kind of suspicious.

A Westerner who can communicate in Arabic? Suspicious.

A tourist who arrived on "Revolution Day"? Suspicious.

A Tunisian in a kashabiya? Not very suspicious.

A foreigner in a kashabiya? Suspicious.

An American Muslim??? Suspicious. He could've been the C.I.A. and a terrorist, rolled into one.

I was told to wait. What did they want with me? In situations like these, I worried I was going to be tortured. I looked at all the national guardsmen who walked past me. Did they look like they could be torturers? A lot of them did. A lot of them had colorless, empty faces. They reminded me of the faces of prostitutes. Maybe the souls of such men and women grew dim, due to the terrible things they did?

Was I going to be killed by extremists for not being a Muslim? Was I going to be tortured for being one?

Four young men arrived. They were mean. They were ugly. They looked like the type of people who would've tortured someone, if it meant they'd have more stable futures.

In an office room, they surrounded me. They looked at me in a way that said they wanted to hit me. They interrogated me, asking me questions like:

"Are you a policeman? Are you in the F.B.I.? Are you the C.I.A.?

"Do you have a phone? Why don't you have Facebook!?"

They asked to see what I had in my pockets beneath my kashabiya. They wanted to see my life's savings, which I had in a swimsuit pocket beneath my pants.

I hated having to do whatever they told me to. When one man told another what he must do, this first man was an enemy.

"that is what war is about: compelling a choice on someone who would not otherwise make it." - J.M. Coetzee

A guy with a pointy pig nose said, "There's something you're not telling us. Something about your story isn't 'clear'."

"How did you hear about this weekend's 'manifestation' in the desert? Is that why you came to Tunisia?"

Manifestation? There was going to be an electronic music festival! I'd seen posters for it all over town. But, I didn't plan on going. "C'est interdit," said the young bully. (It's forbidden.) "C'est interdit pour les gens de votre categorie." (It's forbidden for people of your category.)

"How did you get from Tunis to Sminja?" They were asking me about my third day in Tunisia. I said I'd taken a train, the train that went to El-Fahss. "There isn't a train from Tunis to El-Fahss," said Pointy Pig Nose. Yes, there was ... I'd taken it! "No, there isn't," said Pointy Stupid Nose. "How did you really get from Tunis to Sminja?"

I felt helpless. I could do nothing but cry. Yet, I didn't do that. It felt awful that these national guardsmen were trying to make me into a criminal.

These four young members of the government mafia stopped questioning me. They disappeared.

I sat around for half an hour, shivering in the desert night. Finally, I was released.

On my way out, I was asked by a gentler-looking guy who seemed to be in charge: "What's your religion?"

"I'm a philosopher. I'm not a Muslim, Christian, or Jew. I'm closer to the Asian religions. Buddhism, or - better yet - Taoism."

A man at a desk said, "Soyez bien-venu! C'est ton pays." (You're welcome here! This is your country.) The "boss" said I was, in fact, not prohibited from going to the music festival and could go anywhere I wished.

He said, it had been for my protection that the national guard detained me.

Was that a joke? Ha ha ha. The boss was a joker!

Leaving the national guard's headquarters, I felt like a zebra being freed from a cage. My chest was hard with stress. I thought about how much safer I'd feel if there were no national guard, military, or police. They operated to achieve the objectives of rulers and law-makers; they used lies, contradictions, intimidation, and violence to torment people who got in their way.

"Everyone wants power."

Amina's husband, Jemel, was working in Haikl Rouissi's shop when I arrived there this evening. He made the above quote, when I told him about the national guard harrassing me.

I wouldn't be left in peace, though, until my host Haikl and I returned to the national guard building. There, we were told we had to register with the police that I was staying in Haikl's home. We rode through town on Haikl's motor-bike, looking for a place to make photocopies of our documents.

As we rode through town, Haikl greeted just about everyone. "Khoo-ya!" (My brother!) they called to each other. According to the Hadiths of the prophet Mohammed ... among the good deeds of Islam was "to greet those whom you know and those whom you don't know." Southern Tunisians were so warm and friendly.

I ate the dates I'd gotten from my brown-skinned peasant friend. I offered them to Haikl, and the guy who made our copies. I offered them to three boys who said outside the copy center, enjoying the Tozeur night. They said, to Haikl:

"Is this the American who became a Muslim? Everyone at the 'souq' (market) was talking about him this morning. Businessmen, tourists ..."

No!!!!! I wasn't a Muslim!

Haikl and I continued to the police station. I still felt stressed, as a result of my time with the national guard. All of the policemen were nice and wanted to talk to me. One of them, Karim (whose name meant "generous and kind" in classical Arabic), delighted in teaching me Tunisia's language; he overflowed with happiness and friendliness. But, I just wanted to go home.

We finished the registration. We waved good-bye to the policemen, who where Haikl's friends. Haikl was calm and happy. Once we had returned to the comfort of his house, he told me:

"I love Christians, Jews, everyone. There isn't anyone on this Earth I have a problem with."

Now, he wanted to ask me a question. I could tell he wanted to make a point, about religion.

He said, "Justin, let's say you're working for an association. The leader dies. He's replaced by a new one. Do you follow the dead leader or the new leader?"

I wasn't sure what point he was trying to make. But, he didn't get to make it. I said I didn't work well for others. And I disliked hierarchies.

In religion. And in government.

When we woke up, it was Friday. Haikl wanted the two of us to go to the "hamam" to take a Friday bath, which was required for all Muslims. After that, he wanted us to go to the mosque to pray and hear the imam's "khutba" speech.

But, I had different plans. Haikl understood that.

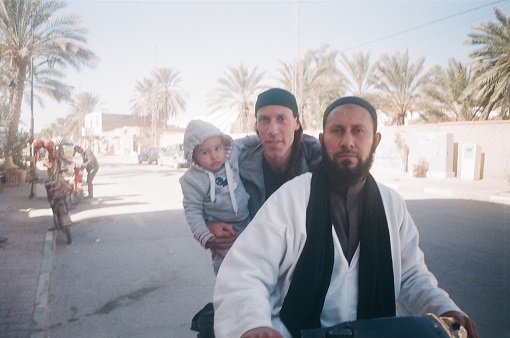

I hitchhiked to the neighboring oasis of Nefta. Friendly, dark-skinned men - one of whom had his head wrapped in a turban - drove me through a flat yellow desert. The desert descended to our left, down to distant date palms that forested the edge of a vast salt lake: the shimmering Chott Djerid.

Cubical, burnt orange houses populated the rising dirt in the town of Nefta. The tall tall pointy towers of mosques poked the sky, here and there. An army of date palms protected Nefta from a sea of sand.

Its yellow medina was similar to Tozeur's. Caged lamps hung over long brick benches, in long brick tunnels that probably stayed cool in summer. The medina's wooden doors, shaped like shields, wore blue paint and decorations made out of tacks: Pac-Man fish and dolphins. I "banged" the heavy knocker of one door, to ask the owner about its "Star of David" design made from tacks. The intelligent, gray-moustached owner said the door had originally belonged to Jews, eight hundred years ago. Was he himself a Jew? No. Nefta's Jews had moved away, he said, to places where there was more work.

Somewhere in the sand dunes to the north of Nefta and Tozeur was a village whose original inhabitants were neither Muslim nor Jew. They believed in The Force. And they included people like Luke Skywalker. This village had been made for the shooting of Hollywood's famous "Star Wars" films. I loved those films.

It was possible in 2014 to walk on "Star Wars" streets through a village of thirty houses. Houses made from geometrical moon shapes: square buildings with spherical moon roofs, connected to one another by diagonal ramps/tunnels that welcomed visitors to the village. Sand piled up against the doors of the houses, which resembled the doors of space pods. The streets were interrupted by Storm Trooper rockets. Sand dunes surrounded the village.

Hitchhiking to the village, I was picked up by Matthew Corosine. One of the organizers of the music festival that would be held in "Star Wars" town, beginning the following day. He gave me a free invitation. And he gave me a lesson on Tunisia's recent political history.

He said, three months ago, all government officials had been removed and new ones were elected, to appease the people who were unhappy with their post-revolution government. A music festival like his had never been done before. His company had originally planned for fifteen hundred people to attend the festival. But now, it seemed there'd be four or five thousand. He thought the festival was becoming a symbol for Tunisian freedom.

At the Star Wars village, Matthew started working. I walked around, pretending to be Han Solo.

And then ...

I walked into the sand dunes and took off my clothes and sat down and felt the sugary sand on my butt. I hoped I wouldn't discover a scorpion this way! My naked body felt the hot desert sun, and the cool winter wind. From the direction of some strong thirsty plants, I heard a bird sing: "Wee, wee, wi-wi-wi!"

I traveled from this uninhabited land back to Haikl's house in Tozeur. My host was doing some extra prayers. He explained, with his smile: "I missed some prayers when I was younger."

I greeted his children, including Emne (10 years old). She had a quieter personality than her two younger sisters. She tried to make her father happy. She could sit and read aloud from the Koran for twenty minutes at a time.

This would be my last night with Haikl. He gave me a religious "kadron" robe and an Islamic skull-cap. He gave me eight bottles of cologne and eight fragrant soaps. One of each for me, my mom, my dad, my brother, and my four grandparents.

Haikl was probably the best-smelling man I'd ever met. And he may've had the warmest heart.

He showed me the wool hoody his dad had brought for Baby Haikl from Libya, and which Haikl now used to wrap his own kids in. Haikl had been friends with his father. This man died seven days after Haikl's son, Mohammed Saaid, was born. Haikl said, in sad acceptance:

"Ca, c'est la vie."

(That's life.)

...

There were lots of reasons why I should've attended Matthew Corosine's music festival.

On Saturday morning, the streets of Tozeur were electric with energy. Foreign tourists explored town, waiting for the festival. An SUV drove down the main street, and a thirty-year-old woman stuck her whole upper body out of the sun-roof; dancing, she waved her arms in victory.

But, I was impatient. I'd seen what I wanted to see of Tozeur, and I was anxious to visit other parts of southern Tunisia. I would, indeed, see more great things ...

And I would meet two French guys who'd gone to the festival. They said it'd been great. The scenery was wonderful. The music was terrific. Everyone was happy, because it rained in the desert during the festival. And all of the Tunisians were in a great mood, because they'd never had a party like this before.

Freedom!

Modern Oddyseus

Thanks to Mohammed Al-Hadi & Mahmud; Feyze; Matthew Corosine; Mohammed & Bilel; and Ryad & Layla for rides!

And much thanks to my brother Haikl Rouissi, Monya, Emne, Meryam, Omayma, & Mohammed Saaid for welcoming me into their home!