"Rest of the World 2013-14" story # 10

ANOTHER BREAK, FOR SOVIET NOSTALGIA

Gori, Georgia

September 24, 2013

A German guy and a Polish girl appeared beside my tent at Nemrut Lake, on the afternoon of the day Riyad the Frenchmen and two Turkish guys had left me. Their hair was so yellow they resembled a dandelion and a daffodil, and I was as surprised to see them in this volcanic crater as I would've been to see a giraffe. We would make a fire this night and stay up late talking. And so, I hadn't remained "bir tane" (only one) for long.

Johannes the German had long, curly hair and a beard. He was a gentle blacksmith who believed in creating communities where people helped one another when they could; but, it frustrated me that I couldn't convince him capitalism was bad. Zuzanna the smaller, quieter Polak especially liked talking about her field of studies: Turkish and Turkish-related languages. She loved dictionaries. She was also a painter, but in order to paint she needed to lock herself up in her room for weeks or months at a time.

Johannes explained that he was hitchhiking around Turkey with Zuzanna "to support her". They were not a couple. Zuzanna had a boyfriend in Poland. Yet, they cuddled together at night, because they had no tent and only one sleeping bag. As I lay in my tent, recovering from the poor sleep I'd gotten the previous night, I was awaken by the sound of Zuzanna giggling. She was laughing at Johannes, as happily and as safely as a child. It sounded like they were having fun.

They reminded me of my belief that loving, celibate relationships could enable people to never grow old. We needed little more than harmonious relationships to live and be happy.

Many people didn't see this. So, they consumed one another, smoked, drank, and did drugs, manipulated and let themselves be manipulated by loved ones, spent their waking hours chasing after money, and moved far from home to big cities to get meaningless jobs with long, incomprehensible titles that impressed some people. They slowly killed themselves, which was harmonious, since they didn't know why they were living.

"People sacrifice the rest of their lives and their dignities for a few moments of pleasure." - J.Breen philosophy (2013)

Pleasure ...

But, why be so opposed to sex? - my brother asked me recently.

Above all, it poisoned society. Causing people to desire or accept monogamy, it took away our freedom. For example: a Turkish girl named Melike recently told her boyfriend she wanted to travel with me; he responded he would break up with her if she did. Their relationship seemed to fall short of "unconditional love" - which had been the subject of Maja from Prague's e-mails to me recently, and which seemed like love's ideal form. In societies with monogamy, we put conditions on the love and support we gave each other. In agreeing to these conditions, we sometimes admitted that we wouldn't be able to express our true selves or reach our true potentials.

Sex led to monogamy. "If sex is great, why won't girls have sex with everyone? !" - J.Breen philosophy (2006)

Monogamy created competition. Those men who couldn't rely on their charisma, wit, or intelligence to "win" a woman would always desire a capitalistic system in which they could defeat their fellow man financially. Child-birth and family responsibilities created further competition. And there was a fine line between competing for dollars and what they could buy, and fighting bloody wars over resources. "Make love, not war!" was a catchy slogan, but naive.

According to Elizabeth Abbott ...

The earliest Catholics were celibate and believed: "Human renunciation of sex could ... re-create the exalted state of the pristine Garden of Eden."

And a Tolstoy character, Pozdnicheff, thought that if sex were gotten rid of, "the aim of mankind (for) happiness, goodness, love" would be realized.

I fell back asleep, after hearing Zuzanna's laughter.

From Nemrut Lake's volcanic crater, I would travel back to Georgia. The reason for this second break from Turkey was that I wanted to visit Armenia.

Two weeks earlier, I'd e-mailed a friend that, "Maybe I'll go to Armenia today." She found it funny that I could just wake up and decide to visit a new country.

I was near Mt. Ararat and the Armenian border at this time, and I'd just learned a visa for Armenia would cost me $8 instead of $50. Eight dollars seemed like the right price for a country I knew nothing about and had no reason to visit. But, in fact, I learned I couldn't visit Armenia this day. The Turkish-Armenian border was nearby but closed.

Instead, I admired the massive bulk of Mt. Ararat and thought up Moses Oddyseus' Fourth Commandment. I was inspired by the fact that Noah's Arc and a bunch of animals had been atop the mountain, even if Moses hadn't:

"Thou shalt follow thy dreams."

And so, I traveled from Mt. Ararat to Lake Van and Nemrut Lake, and from there back to Georgia. I was led by a desire to speak Russian with exotic Armenians.

I was fueled by delicious Turkish food:

A guy named Bearded Borhan invited me to share in his family's picnic, beside Nemrut Lake. We ate fresh onions, tomatoes, long slender peppers, and grilled slices of eggplant from Borhan's garden. We ate chicken thighs grilled with spicy red juices my lips couldn't forget for weeks. We put all this inside flat rectangles of fluffy fresh bread.

A restaurant gave me free "mercimek" (lentil soup) just because I asked, "Kac para?" (How much does it cost?) The creamy bowl of soup came with a loaf of the softest bread to dip in it. It was delicious and filling, and normally cost $1.60.

Near Georgia, I befriended a Kurdish shepherd. He milked his sheep and gave me two liters of milk. The thick and dirty, foamy milk left a film of sweet cream on my throat and teeth. It had a strong taste of nutmeg. The shepherd gave me liquidy but solid cheese which was firm yet crumbled between my teeth. It smelled spoiled and alive, like wine.

People in Turkey were hospitable, as were Georgians.

The two neighbors were similar in some ways. For example: both considered it essential to have and maintain a family, and independent people were mysteries to them.

But, returning to Georgia, I felt much more comfortable. Turks and Kurds sometimes looked at me in ways I didn't trust.

I had a great conversation with Georgi, the first Georgian to give me a ride as I headed for Armenia. This government worker claimed that his countrymen had "nikogda" (never) wanted to be in the Soviet Union.

Nevertheless, the communist inside me was nostalgic for the U.S.S.R. I couldn't resist the opportunity to visit the hometown of a Georgian who'd led the Soviet Union for three decades: Joseph Vissarionovich Dzugashvili, a.k.a. ...

Stalin.

On December 18, 1878 he was born in a small house that stood today. The two rooms inside it were surrounded by raw wooden doors and windows and a porch with three steps leading down to the ground. The rest of its wooden facade was white, but its hind structure and its base and the steps leading to the cellar were made of gray brick. I pushed on the cracked glass of the windows, trying to reach the warm and dark interior where little Joseph Vissarionovich had lived until age four.

I visited the large museum dedicated to him.

He'd known at age fifteen he wanted to be a revolutionary. In 1901, he led his first demonstration. Tsarist Russia began exiling him to distant places like Siberia. He began escaping. A painting represented Stalin at age twenty-two: with bushy flowing hair, a clean bushy moustache and beard, and a wool scarf covering his neck, he had the eyes of a confident poet.

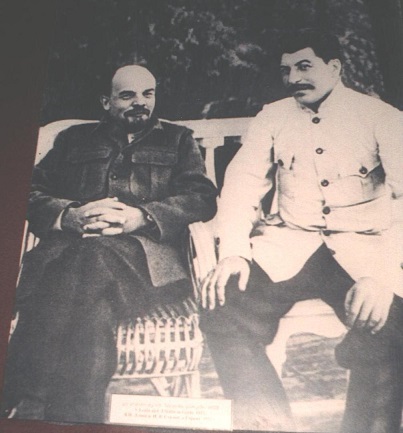

He began writing to and meeting with Lenin. The museum displayed a copy of Lenin's book, "An End to Capitalism in Russia." The Bolshevik Revolution was successful. A photograph from 1919 showed Lenin, Stalin, and Kalinin together. Stalin, with his firm eyes and peaceful "fu manchu" face and warm Russian hat, resembled a loveable bear. Lenin, with a long long bushy moustache and a gray pilot's coat and police hat, looked like an out-of-fashion taxi driver.

A later picture of the two showed bald Lenin with a guerrilla "fu manchu" moustache. Fatter, bushy-moustached Stalin stood with an unsympathetic, impatient pose. Around this time, Lenin was helping to choose the man who would succeed him as the Soviet leader. He recommended someone "more patient, more loyal, more trusting, more cooperative, less capricious" than Stalin. He called Stalin "grubyy" (rude).

Of course, Stalin would go on to lead the U.S.S.R. from 1923 to '53. The museum said nothing about the ten to twenty million of its own people Stalin's regime had killed. It painted him in a good light. I overheard a museum guide insisting to her tour group: "On spas mir od fashizmu!" (He saved the world from Fascism!)

"The tough, unique, heroic, and famous struggle of the Peterburgians against the enemy blockade is linked to the name of Mr. Stalin," a Russian said during World War II. Georgian soldiers wrote inscriptions reading: "We're dying, but we're not surrendering," and, "For our nation, for Stalin."

Stalin's eldest son, Yakov Dzugashvili, was captured by Germans during the war. Stalin didn't free him in order to show an example to the country that they needed to free their nation. Yakov said: "If I don't ever see my nation, please tell my father I never betrayed him." Yakov died in a concentration camp. And Germany was forced into an unconditional surrender.

The Soviet Union had won. But, in the last pictures of Stalin, his dark eyes and firm face seemed to lack feeling.

I stepped outside of the museum. Actually, I would encounter no more Soviet nostalgia than that.

But, I began to think that Georgia was one of the world's perfect countries.

Its public statues were creative and interesting. Its cubical houses, new and old and ideally wooden, were beautiful with second-story balconies. I loved Stalin's hometown of Gori, where a long pedestrian plaza stretched past fountains, trees, and benches toward green mountains in the distance. I met two teen-age girls who told me Georgian "lovers" only held hands and didn't kiss until married. I liked that it was safe for them to hang out with their older guy friends at night. I admired Georgia's innocence.

I went to see the Caucasus Mountains. I traveled past a sort of Easter Island statue with five faces on each side of it and spears coming out of its head. My driver said it commemorated the time three hundred Georgians had defended their mountain pass from thousands of Mongols.

I tried to climb a mountain. It was steep like a knife, rocky like a cliff, spiky at the top like a porcupine. Large, "whoop!"ing birds ran across its loose rocks. This mountain sat on the opposite side of the highway from giant Mt. Kazbeg, the mountain the Slovakian hitchhikers, Ondrej and Barbora, had wanted to climb. They ultimately didn't make it there. And I failed to climb my mountain, because I was still weak with diarrhea.

I finally gave up on my body healing its own self and went to a pharmacy. I continued towards Armenia.

Two Russians drove me over the "Mountain Pass of the Cross". In 1697, a Russian army had come through this pass in order to help the Christians of Georgia. The Turks, apparently, had just killed 100,000 Georgians who wouldn't convert to Islam.

Not all Georgians were appreciative of Russians, however.

A man named Zurab would give me my next ride. His messy car stunk of body odor. He looked at me with gentle eyes and flicked his neck with his middle finger. This signified, in Russia or Georgia, that he'd been drinking. The gesture always reminded me of a fish with a hook stuck in its gills, and it made drinking seem even less appealing to me than usual.

He spoke little Russian. After a few minutes of silence, he pointed to the hills to the north and said, "Russian (military) base." More silence followed. Then, he pointed out a second Russian base.

He began talking about Russian planes bombing Georgia in 2008. "Okupatsia," he said. (Occupation.) Russia now controlled land to the north that used to be Georgia's.

He spoke about Russian, Kazakh, Chechnyan, and Abkhazian soldiers cutting off a Georgian soldier's head and playing soccer with it. He couldn't stop talking about this, couldn't stop thinking about it. I was pretty sure I heard him say, "Sadists."

He spoke about a war in 1992 with Abkhazia, a territory which Georgia believed was Georgia's. Had he fought in these wars? I asked. He let me know he'd done so as a "Georgian" soldier. I tried to smile at times to lighten our conversation. He never did.

He dropped me off in the Georgian capital, Tbilisi. My last stop before Armenia.

Tbilisi's "old town" was full of wooden houses with flat faces or rounded facades, all of them with romantic balconies. Baby blue houses with dirty white balconies. Yellow houses with black balconies. Peach. Pink. Dark oak. Swamp green houses with diamonds on their balconies, covered in ivy. A stone and brick clock-tower was decorated with gold grape-vines and oil paintings of birds, a rural home, a Tbilisi snowstorm.

Tbilisi was a fine capital in a fine land.

But, what would Armenia be like?

Modern Oddyseus.

Thanks to Serkan, Hasan, Emra, & Nurel; a van of female teachers, including Esra; Mehmet & Erdugan; Masallah; a mini-bus in Mus; Dohan & Zafer; Fati & Kereb; Jamal; Egrem & Ali; Abdul Kadir & Shah Senin; Cevdet; Murat & Nurula; Yakub & Kursat; Sefa & Yasar; Bulent; Mehmet, Turgay, & Ramazan; Georgi; Matan & Avi; David & Dato; Tango & Beso; Mary, Zeynal Tuzcu, & Gia; Zuraba; Mukhtar & Alik; Lena & Roma; and Zurab for rides!

"I exploit you, still you love me

I tell you one and one makes three

I'm the cult of personality

Like Joseph Stalin and Gandhi." - sung by Living Colour