"Rest of the World 2013-14" story # 8

PEACE MARCH IN KURDISTAN

Mt. Suphan, Turkey

September 6, 2013

After visiting Georgia, I planned to hitchhike to Lake Van in southeastern Turkey and look for a teaching job.

Turkey's eastern and southeastern land was home to a predominantly Kurdish population. Kurds weren't Turks, they weren't Arabs. They were Kurds. Their origins dated back thousands of years. Those Kurds who currently believed in Kurdish independence, and many tourists, called their land: Kurdistan.

The land stretched into four countries. A Kurdish teacher who'd given me a ride near Istanbul told me, "Dort imperialist memleketler: Turkiye, Iran, Irak, Soriye. Bir buyuk imperialist: Amerika." (Four imperialist countries: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Syria. One big imperialist: the U.S.A.) He said these countries wanted Kurdistan's oil and fresh water.

As I traveled through Kurdistan this late August, I felt the land looked depressed. In the countryside, people lived in unaesthetic homes made from concrete blocks. Some led their cows and sheep to graze, but otherwise it looked like they didn't have much to do.

The climate itself seemed harsh. The forests and lakes of northern Turkey didn't exist here. It was arid and windy. The rivers barely flowed. The sun was hot. I felt uncomfortable.

My travels took me to the town of Igdir, pop. 100,000. Brown-skinned men with moustaches, of all ages, called me to them. What a friendly town. A businessman wanted me to be his partner on a gold-seeking expedition to Mt. Ararat. Younger men just wanted to talk. "Apo Ocalan." They proudly repeated the name of a Kurdish leader serving ten years in prison.

A man named Serhat Cakmak offered me a place to stay. His ancestors had been Armenians but had to assimilate and become Kurds. Now, Serhat's parents mostly spoke Turkish at home, because it was the language of opportunity.

I observed Igdir's streets by night. Young men acted macho, pretending to run over each other on their motorcycles, and making gestures of male dominance.

In the morning, I hitchhiked out of Igdir. I wanted to visit the 17,000-foot pyramid of Mount Ararat, which stretched into its mask of clouds near Igdir. I wanted to climb the mountain, like Moses. I wanted to come back down with ten new commandments, to include things like:

"Thou shalt not judge nor condemn others, nor believe in a God who does."

"Thou shalt not make nor enforce any laws."

"Thou shalt question everything."

But, I wouldn't do that. As I passed the point where I needed to take a small road up the mountain's barren slope, I saw two Turkish tanks pointing their cannons at the mountain and soldiers looking through binoculars.

I already believed Turkey to be a highly militarized country, full of "askeri" (soldiers). It was no doubt more militarized in Kurdistan, where there was opposition to the government. And Mt. Ararat was near the borders of Armenia and Iran. I decided I didn't want to climb the mountain badly enough to get shot by a cannon. Besides, Moses had gotten his commandments on Mt. Sinai.

I continued south with my driver, Abdul Gani, who could take me all the way to Lake Van. This dark brown Kurdish man transported steel long distances, earning $450 a month to support four kids. "Calis yok Kurdistanda," he said. (There are no jobs in Kurdistan.)

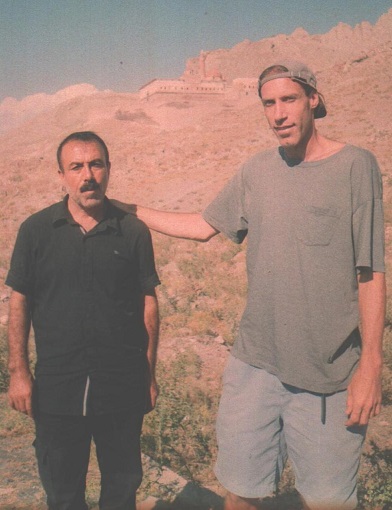

He was sophisticated and intelligent. He said, "Tarihi seviyorum." (I like history.) He took us to visit Ishak Pasa Sarayi (Ishak Pasa's Palace). We drove upward towards a wall of arid brown mountains, with their rocky swords stabbing the sky above. The spherical roof of the palace, made of cherry red blocks, supported orange minarets that looked stunning beside the mountain-tops. The palace door was decorated with an inverse honeycomb design. A "tomb" led to an underground chamber where Ishak Pasa, a Kurd, had been buried two hundred years ago. Abdul Gani and I went to a restaurant that looked down upon the arid town of Dogubayazit, near to Iran, and we ate dry meat off a sheep's ribs.

In Ishak Pasa Sarayi, prisoners used to be lowered by rope through a narrow hole into the dungeons. Abdul Gani told me, back in his work truck, that he'd spent ten years in prison. Why? "Konusma." (Because of something he'd said.) The Turkish government didn't allow freedom of speech.

I asked, "Sen devrimci mi?" (Are you a revolutionary?) He smiled and said, "Evet." (Yes.)

He said Turkish history was "yalan" (lies). It was all about one man: "Ataturk, Ataturk, Ataturk ..."

There were forty million Kurds in the world, he said. I was surprised to see that, in the towns we passed through, all signs were written in Turkish. Kurdish wasn't allowed.

We passed from the towns to hilly mountainous terrain. My driver said guerrilla rebels from the "P.K.K." - a Kurdish terrorist group that had killed 30,000 Turks in its history - moved and fought in these mountains. We passed fields of broken black rock, and Abdul Gani explained: "Yanardag." (Volcano.) I asked: Did the Kurdish rebels want independence? He said, no. "Demokrasi."

We turned off our main road so my driver could visit some friends. We came to four guys in the middle of nowhere, who seemed to be operating a small oil-drilling machine. They seemed gentle. I couldn't communicate with them. Abdul Gani explained later that they were Syrian Kurds, who'd come to escape their country's war.

He dropped me off beside Lake Van. I wanted to camp on a mountain nearby. He said it was too dangerous. Did I have to worry about the P.K.K.? No. He said I had to worry that the army would think I was the P.K.K. He told me to camp on the beach, instead.

I'd wanted to visit this lake ever since reading about it and seeing its picture in a book, "Natural Wonders of the World." It sat at 5300-ft. elevation and was sixty miles long by sixty miles wide. I hoped to find lots of birds there, and pink flowers on the shore. I'd read about Van Kedisi cats, which had one blue eye and one green eye and loved swimming. Legend had it a "canavar" (monster) lived in the lake.

I arrived here after five straight weeks of moving around. My body needed a break from carrying my bags. I was in the middle of two straight weeks of having diarrhea. I was ready to settle down in a community and develop long-term relationships with people.

But, I didn't fall in love with Lake Van. The deliciously blue water was, in fact, salty and oily. A strong wind dried out my skin. The lake and land were barren, of birds, fish, trees, monsters. I felt rude speaking Turkish to the Kurds. I decided I wouldn't look for a job here.

Something better would happen.

A "Peace March" to the top of Mt. Suphan, not far from the lake, was planned for September 1st. I wondered if this event had something to do with the P.K.K.'s announcement that, if negotiations with the Turkish government didn't improve, they'd end their temporary peace on September 1st and begin fighting? I joined the Peace March, along with a hundred and twenty people. This would lead to me not having to hitchhike nor carry my bags for a while, and to being with like-minded people. Hooray!

On August 31st, we were driven to "base camp" and given food. We woke up in our tent at two a.m. We were led through darkness and wind up the barren mountain. I was happy to be guided, by our pony-tailed organizer named Adem Gul. We took slow steps, and this made it possible for my ill stomach to survive.

Turks and Kurds, young and old, were making the climb. The most inspirational climber was a guy with a wounded foot, who pulled himself on crutches. The coolest climbers were dusty-skinned Kurds wearing paintbrush moustaches, aviator sunglasses, and towels wrapped around their heads. A fraction of the climbers were women, many of whom were short and energetic and gorgeous.

At eight-thirty, we ate breakfast and looked down on Lake Van. Then, we spent ninety minutes climbing up a giant metropolis of orange boulders. We reached the highest rock, at 4058 m. (13,400 ft.) elevation. Yay!

I celebrated with my new friends: Servet, a guy from Istanbul who dreamed of running ultra-marathons, and a female teacher named Ayse. My eyes grew wet when I watched the guy on crutches push through the crowd so he could stand on the top of Suphan.

A guy named Kenan drove me and blond Ayse and two other females to a mountain lake. I was a lucky guy. Kenan would even give me a turquoise jersey from Turkey's "Fenerbahce" soccer team.

We visited a graveyard from an ancient civilization - an army of orange stones, with hieroglyphic writing on them, that stood up and looked at us. I liked it. And then, we drove up into a large volcanic crater. I hoped to stay here and write a few days.

Inside the large crater were a forest of aspen trees, maple trees, birds, tortoises, hedgehogs, and blue Nemrut Lake full of drinkable water. It was perfect. A forty-eight-year-old woman named Asuman (meaning: "Sky") was the first from our group in the water.

Thin Asuman wore very long hair, a swimsuit, and an eagle necklace. She'd told me eagles and horses were her "totem" animals that guided her. She liked to think of herself as flying through the sky.

The last member of our group was a girl named Melike ("Meh-lee-keh"). She was independent and beautiful. She made a sad face, though, regretting that she had brown eyes and not colored ones. I told her my brother loved brown eyes.

Melike was happiest when swimming in the cold lake, talking about traveling and hitchhiking, and being picked up in the air by me doing dance moves. Asuman told her she should stay at the lake and travel with me. Good idea, Asuman! Melike didn't have time, though.

I felt that being with these people, even for a short time, was good for my health and my stomach. Kenan and they girls left. Three other hitchhikers from the "Peace March" arrived.

A Frenchman of Algerian descent, Riyad, and two Turkish guys, Yunus and Alper, were traveling separately but had come here together. We camped together and stayed up late talking in our tents.

Darker Yunus and white, black-bearded Alper were afraid of bears and wild pigs. My funniest memory of the night came when the Frenchman said that people weren't supposed to be "korku" (afraid) of pigs, pigs were supposed to be "korku" of humans.

It was nice to have Riyad around during our Turkish conversation, because we could help each other with words we didn't know. Alper was easy to understand, though. Riyad went so far as to say he had a nice voice. It was nice to fall asleep to ...

Zzz.

peace,

Modern Oddyseus

Thanks to Ahmet & Cazim Simsek; Senturk & Verdan; Abdul Gani; a weird guy; Cazim; Barum & another guy; and Sunayman for rides!

Much thanks to Serhat Cakmak; and Adilcevaz's student hostel for places to stay!