"Rest of the World 2013-14" story # 6

A TOAST, TO THE KOBALADZES

Kobuleti, Georgia

August 30, 2013

"In keeping with the tradition of the great people of Georgia, I the Modern Oddyseus would like to propose a toast.

"On my third night in this country to the north-east of Turkey, I was told by a man named Nukli that Georgian culture 'begins at the table'. Nukli was dark and successful, in a rough-looking way, and he spoke to me intelligently in Russian. 'At the table,' he instructed me, 'the oldest man is the most important.' He and seventy-eight-year-old Nodari and others at our dinner table would be giving long and heart-felt toasts, and we were expected each time to finish the vodka or "cha-cha" (a liquor made from grapes, with 68% alcohol) in our shot-glasses.

"Nukli told me, 'A rich man has a good bed, meaning a beautiful wife. But, a poor man has a good table.'

"I sat in poor Badri Kobaladze's kitchen in a village, at a table with five local guys, and it felt like we were getting ready to discuss the most important secrets of the world.

"Across from me sat Zauri Xalvashi. This dark and thin twenty-five-year-old was all bones and stomach muscles and a voice often raised in anger.

"It was he who had seen me in my tent the previous morning and invited me to his house. He'd moved in with his in-laws after marrying Nino Kobaladze. Their two-story house, with six rooms branching off a large opening on each floor, was built for many people. Growing corn and vegetables and grapes, and wandering cows and chickens and ducks, surrounded the house. All of this was surrounded by similar houses, most of them owned by Kobaladze parents or siblings or cousins.

"On that morning, thin and pale, auburn-haired Nino presented me with food of all kinds. Corn. Vegetables. Vodka. Cheese shaped like soap. Tea. Hazelnuts dipped in honey. Bread. A seedless, prune-like fruit coated with sugar water. Pears. A bladder-shaped fruit called "ingir" which contained sweet, pink flesh. Enjoying Georgia's famous hospitality, I stuffed myself with home-grown food.

"I told them, 'You live good here.' They said, 'We lived good during communism. The Russians saved us from the Turks, who killed us if we didn't give up Christianity and become Muslims.'

"As I ate, twenty-two-year-old Nino sat with her timid daughter and unstoppable son. She taught me Georgian. 'Madloba' meant: Thank you. 'Kamarjoba' - Hello. 'Kargat' - Good-bye. She taught me other words, and I noticed many rhymed. 'Kali psali tskali,' I said. (Girl pear water.) Nino laughed. She laughed very freely, which made it fun to have her around.

"So, let's drink to Zauri and Nino and four-year-old Mary and little Sandro. Kamarjoba!

"Wait. Not yet. Georgian toasts don't end so easily.

"Sitting next to Zauri, on my third evening in Georgia, was Zauri's father Avto. He was a less passionate, white-haired version of Zauri.

"The previous day, I had also joined the Kobaladzes for lunch. Georgians were always prepared to have more guests at their table. We ate grilled loaves of mashed corn, called 'jadi' (a good rhyme for 'kali'!). They tasted good with a thick, sour milk called 'matsone'. With bread, we ate chicken and onion and red peppers in a red pepper stew.

"As we ate, we took four shots of vodka. Each time, Avto made a toast. He toasted to: our health; peace in the world; our nations; and this lunch.

"And so ... here's to Avto Xalvashi! He'd come over from his neighboring village to put in the Kobaladzes' new bathroom. What a guy! Kamarjoba!

"Let's go again to my third night in Georgia.

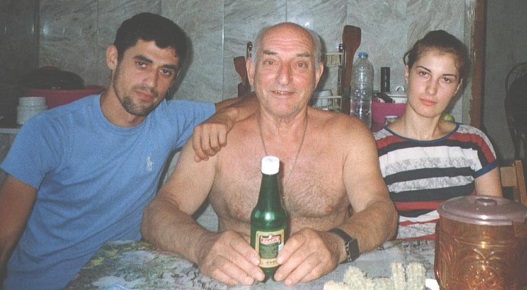

"Sitting across the table from Avto was a man with the white hair of a bald eagle with nothing on top, a sharp nose, a happy silly smile and big clear eyes, and a strong body with a big gut. He was our most important person, Nodari Lazishvili.

"He'd been seven years old in 1941, when the Soviets joined World War II and his dad was sent to fight. In 1944, Nodari's father was captured by Germans. He was released in 1945, but was immediately imprisoned by Stalin for ten years for having fallen captive to the enemy. In 1954, Nodari began his army service. He came home three years later and was told by a family member, 'This is your father.'

"Nodari's stretching smile, pointy nose, and wide eyes leaned toward me, as he described his confused feelings upon seeing a father who'd disappeared.

"Nowadays, Nodari was happy and strong. On the day I'd eaten lunch with the Kobaladzes, he carried one of my heavy bags as we walked to the river for a swim. I'll never forget the image of this man in his bathing suit, with his proud gut and his silly face surprised by the speed of the river, as dark clouds haunted green mountains in the distance.

"So, let's drink to Nodari! He's a Kobaladze because his niece married Badri. Kamarjoba!

"Badri Kobaladze, on my third night in Georgia, sat to my left. This short, round man wore hazel hair and beard stubble on a face darkened by work in the countryside. He had only three upper teeth because he liked sweets, and his smile was a warm and jolly one.

"He'd told me the previous day that he was ashamed I'd slept in my tent when his welcoming home was nearby. His friendly and humble voice asked, 'Aren't you afraid of snakes? I'm afraid of snakes!' He invited me to spend a night or two at his house any time.

"His wife, Neli, was a short and strong woman with auburn hair. She could often be seen walking around outside, calling to her cows and quacking at her ducks, to make sure they were safe.

"In addition to a great wife, Badri Kobaladze had a great car. I'm not talking about the red compact 'Moskvich' (manufactured in Moscow) that he had to push to start. Nor did he own a square-edged 'Lada' like many guys in the former U.S.S.R. His prize was a 'Volga' (made in Volgograd). It resembled an early-1900s Ford, with polished black curves both fancy and elegant. Badri told me Volgas had been used to carry around families of Soviet political leaders. This particular one had belonged to the prime minister, Brezhnev.

"So, let's drink to Russian cars. I love them!

"Wait, wait.

"I just wanted to add that, on my second day in Georgia, I carried my bags through thigh-deep water in the river Nodari and I had swum in. I reached an island. I put up my tent and spent the next twenty-four hours sleeping or writing. During most of this time, showers of rain bombed the earth. The river rose. I was soaking wet. I was lucky to find a place where I could carry my bags across a rocky riverbed through racing, knee-deep water and reach mainland. I walked to Badri Kobaladze's house, where I was given dry clothes and shelter.

"So, here's to Badri and Neli. Here's to their two chickens who were killed by a 'zarli'. That stupid homeless 'zarli' (Dog - or a pretty good rhyme for 'psali') was always following me around. I felt terrible. ....

"Kamarjoba!

"On my third night in Georgia, Nukli and Nodari did all the toasting.

"We ate abundantly. First, Nukli interrupted dinner and spoke about my long trip to come here. We drank to whatever it was that had brought us together.

"Next, Nodari had us drink to the hope that everything would be good for me.

"Nukli had us drink to Badri, the only one of his friends who'd remained. He said Badri would never harm anyone.

"We drank to our children. We drank to our parents and grandparents. Finally, Nodari gave a long and rambling toast in which he kept repeating to me, 'Compare Georgian culture to Turkish culture. See what you find!'

"Thus far, much poorer Georgia was more hospitable.

"I asked if they'd preferred life in the U.S.S.R. to the current system, and they quickly said: 'Sovetsky Soyuz!' (U.S.S.R.!) Nukli said, calmly, that the U.S.S.R. had been better for 'prostoi lyudi' (simple people).

"Badri said, 'In the U.S.S.R., everyone had two cars.' (He had two cars now, but the Volga didn't run.) 'Gasoline was practically free. Everything was cheap. If you worked two years, they gave you an apartment. If you worked a while longer, they gave you a car.'

"Our conversation turned to Joseph Stalin, the most famous Georgian.

"Nodari insisted, 'He worked for a salary! He died poor, in a shirt and slippers. His family got nothing!'

"Nukli said, 'I admire Stalin because he won the war (WWII).'

"At one point in the night, Nodari suddenly turned to me and said, 'Billa Clintona ya ubyu!' (I'll kill Bill Clinton!) Why? 'Znichil Soyuza.' (He destroyed the U.S.S.R.)

"I explained that he'd make better use of his energy if he killed Reagan or George Bush Sr. instead. He also threatened to kill Mikhail Gorbachev, who he said was living in wealth these days.

"And that about did it for my third night in Georgia.

"And that about does it for my toast. Let's drink to the people of Georgia. Let's drink to the Kobaladzes! ... the ones mentioned here, as well as all their parents, cousins, neighbors, wives, a wife's sister who could speak English, a niece who cooked me a cheesy eggplant-red-pepper dish, and friends who visited us or whom I visited during my three days with them.

"Kamarjoba!"

Gulp.

"Oh man, that cha-cha is awful."

Modern Oddyseus.

Thanks to Selat; Goksu & Yavuz; six Turkish guys; and Zuraba for rides!

Much thanks to Badri, Neli, Zauri, Nino, Mary, Sandro, & Nodari for the hospitality!