"Western Africa" story # 25

COMMUNAL BY NATURE

Bubaque, Guinea-Bissau

October 11, 2012

"Po tudu tarda ki tarda na iagu i ka ta bida lagartu." (A Creole saying.)

Translation:

The trunk of a tree, no matter how long it stays in the water, doesn't become a crocodile.

Its meaning:

A European, no matter how long he lives in Africa, can't turn into an African.

This saying served to point out that, although I'd written that I was "becoming Bijago", I meant this as a form of acculturation and not of assimilation. "Acculturation" - as described by Father Luigi in one of his writings I was preparing for the internet - was a normal process in which a person learned from another culture in order to add to his own. "Assimilation" was an abnormal process in which one embraced the attitudes of a foreign culture while losing his own identity.

I was learning from the Bijagos, yet I remained a Michigander. ... a person who valued fun more than wealth, who believed in the existence of the word "funner", who supported the Detroit Tigers' baseball team, who hunted deer, who fished in small black lakes and swam in great blue lakes, who'd grown up sledding during long dark winters, who baked pies.

That's what I was. And the Bijagos were Bijagos.

Besides, there was one thing which they did a lot of and which I didn't agree with. They begged.

They did it casually, most of the time. They saw someone whom they figured had some extra change, and why wouldn't that someone want to share it with them? They wanted bread, in addition to their rice and fish. They wanted entrance fee to see the soccer game. They wanted some more wine.

As long as the thing they wanted didn't require them to work or save money, they wanted it.

Some of these beggars were twenty-year-old men, still in high school, who wore fancy (or, at least, immaculately clean) Western clothes and carried cell-phones. Assimilating to African-American culture, they sagged their pants. They were nice people. But, if I ever saw any of them working, it looked unnatural.

It was tough to believe, but in the world's fifth poorest country, the young men seemed spoiled.

Life wasn't that bad here. There was plenty of food, things were cheap, people worked little, there was plenty of caju wine, there was support for soccer, sports fans enjoyed baobab ice cream at the games ...

Only elderly women and mothers with babies ever looked pathetic when they begged. They claimed a need for food or medicine.

I was told by some whites that it wasn't just us who were begged from; wealthy Guineans were constantly begged from, too. I believed this.

Other whites claimed the Bijagos took, took, took, but never gave. I disagreed with this.

The Bijagos couldn't give to you, if you lived isolated from them. But, on my recent trip to visit my old neighborhood, three Bijago families insisted I eat with them: rice dishes that included mandioca or pork.

My girlfriend Patricia - despite the fact that she only owned one chair which had no back and whose legs often collapsed beneath people - invited everyone who passed her house to eat with her.

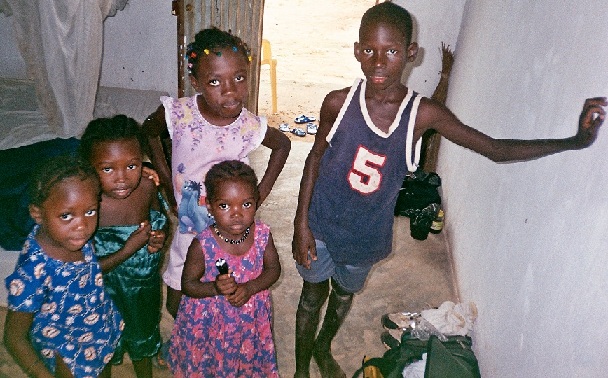

The Bijagos came from a culture that was based on the unity of the village. Traditionally, they had no money. Individuals were allowed to own fruit trees and certain crops and livestock, but well-off people were expected to share with the less fortunate. The elderly, it seemed, were able to ask anyone for anything at any time and be granted it.

Father Luigi's anthropological work on the Bijagos stated: "The refusal of food to a hungry person or to grant any help solicited ... is the most serious offense, and the people believe this action can lead to one's own death."

Another Creole saying said: "Bianda ora ki kusidu i ka ta ten donu." (Warm food has no owner.)

And there was a famous story of the Bijagos'. It told about Difuntu women.

Difuntu women were girls who endured the Bijago mens' initiation rituals. They did this in the name of boys who had died before fulfilling this obligation. The girls became "possessed" by the boys' souls, as they danced and sang to the bombolon drum.

The Difuntu women were free to beg for their food. Some people believed, part of the reason for the Difuntu women's existence was to teach others the lesson of giving.

In the famous story, one man refused to give them food. He only had enough for himself and his wife. The Difuntu women said:

"Why is it that you only share with your wife? Aren't we all brothers and sisters in the village?"

I agreed with that point of view. A community's members must've had an enormous faith, if they were able to give away anything at any time without a worry that they were going to need it.

Or, maybe they didn't have much choice? In the past, young villagers who hadn't gone voluntarily to attend the long and painful initiation cerimonies in the forest were carried there by force. I wondered what happened to those who didn't share?

Unfortunately, I did not have the faith of the sharing Bijago villagers. I was too darned capitalistic. A typical Michigander!

I gave only to those people who'd shared their food with me. I also invited people to eat, if they were in my home and I'd cooked recently. I also gave gifts to people who'd been nice to me, if I had the time. But, that was about it.

I liked to believe I was communal, unselfish. Modern Oddyseus' Travel Annals - my life's work! - would remain free for the world forever.

But, it seemed to me, if it was the Bijago people's desire to share, they shouldn't desire a society that used money.

Forced to use money, I saw it in a sense as my health. I saw it as my energy to achieve my individual goals, to guarantee I had food on days I wanted to write. I didn't need much money, but I needed some. I'd had $14.20 left when I'd found my job here. If I'd had even $1 less, I might've left the Archipelago of the Bijagos before Father Luigi had hired me.

Besides, I believed giving to beggars encouraged people to be pathetic, rather than empowered them.

For example, tons of clothing and medicine were donated every year from the West to Africa. The result?

Africans bought cheap Western clothes instead of making their traditional African clothes. This exchange robbed them of their self-determination, identity, and the pride of accomplishment.

Africans bought cheap Western medicine instead of consulting local healers. Poor families suffered and died, in attempts to save money. I doubted the Western medicine was always better. Local wisdom was being lost.

At last, it should be said that not all Bijagos begged. My neighbors from my first neighborhood had wanted nothing but friendship. One woman sat in front of her tiny mud hut all day, with her alcoholic husband and stunted nine-year-old daughter; she talked to me in Bijago, but never begged.

Not giving to beggars, I could still sleep easily at night. This was rainy West Africa, where nature gave to all in abundance.

A fourteen-year-old friend, Edinesio, said with his usual enthusiasm:

"I'll always eat here! If I'm hungry, I'll go to the beach, catch four crabs, my hunger will be gone. I'll eat three shellfish, my hunger will be gone. I'll eat four yellow fruits, my hunger will be gone.

"My uncle went into the jungle once. We didn't see him for two months! When he came back, his hands were full of chabeu fruit."

from the Michigander Bijago,

Modern Oddyseus