"South & East Africa 2011" story # 12

BIG TRIP (AROUND THE MOUNTAIN KINGDOM)

Katse, Lesotho

May 9, 2011

I was told one day, while selling stories in Maseru, about a horse-riding trek in the high mountains of Lesotho. Seeing as how it was already late autumn, and there'd already been frost on the ground in the lowlands (which were still about a mile above sea-level), I foresaw the story of my coming trek would be called: "Horse Riding with Snowflakes". I envisioned myself being very happy in the mountains.

Zach, the Peace Corps volunteer whom I met in Maseru, told me of another volunteer who I could stay with in the countryside. Last Monday, a week after I'd worked hard to save money for the horse-riding, I took off from the lowlands in order to explore Lesotho.

Two men, who worked for the government delivering wood and coal to health clinics, drove me from the western lowlands to the circular country's center. I ascended the winding, nausea-inducing road above the Mohale Dam again. I passed the beautiful, "African Clown" houses (black, shaggy-haired huts with white-outlined doors and window eyes) again. The many bare, grassy mountains became boring. Shepherds and their flocks partially obstructed the road at times. My drivers called them names and laughed at them.

I made it to the village of Katse (meaning: "Cat") after dark. I had no phone nor any idea where my Peace Corps host was staying. But, I wasn't worried. Surely, everyone would know and could show me where the "lehoa" (white person) stayed. A young boy quickly led me up the dark hillside to the hut of American Mike. In the candle-lit hut, Mike (known locally as Nyakalo: meaning "Happiness") warmly welcomed me.

I was so happy to be staying in my first rondavel, a.k.a. hut!

The clay walls were naturally orangish, as if pleasantly painted. It was furnished with a bed for Mike, a rug for me to sleep on, a wardrobe, a desk and small cooking stove, a spice rack that hung from the ceiling, and pictures and maps on the rounded walls. The thatched roof would keep the rondavel warm in winter.

Mid-twenties, bearded Mike introduced me to a new tradition of his: whenever someone visited him, he had the visitor draw with him on a blank sheet of paper. I enjoyed this very much. Our drawing included an orange-and-green, flying, Abraham Lincoln dog preparing to eat a slice of pizza and ice cream cone.

The next day, Mike had work to do. On his flexible Peace Corps agenda was: meet with the village chief, teach a women's business course, and slaughter a chicken.

I greatly enjoyed waking up in and walking around the village. On the cold and dark slope of the early morning village, Mike and I greeted people: happy-faced guys wearing blankets; women who stayed close to home, near steaming pots that cooked the day's vegetables.

"Lumela, 'me!" (Hello, ma'am!)

"Lumela, ntate!" (Hello, sir!)

"U phela joang?" (How are you living?)

"Ke phela hantle!" (I'm living beautifully!)

While Mike did his volunteer work, I descended to the reservoir created by the Katse Dam. Unlike the Mohale Dam's blue, lake-like reservoir, this one was black and very long and fjord-like. I swam above the depths, beneath the hot sun.

That night, we ate the chicken Mike had slaughtered, in the house of the local family that hosted Mike in his hut. The family played loud music on a stereo powered first by solar energy, then by a car battery. After dinner, we all danced as a family.

Sotho music commonly featured the vocals of a fat, gruff man, who yelled to slow and repetative accordian music, which was accompanied by the "tap-tap-tap" of a wooden drumstick.

The family's tiny five-year-old daughter, Bobo, hunched over like a grandma and stumbled left and stumbled right to the music. This was one way to dance to Sotho music.

Eleven-year-old Thabo, a 100% pleasant boy, also hunched over; he pulsated his shoulders and shuffled his feet "1, 2 ... 1, 2 ... 3" to the music. Mike, a.k.a. Nyakalo, also pulsated his shoulders, but he stood tall and held his arm as if brandishing a shepherd's stick. These were other ways to dance to Sotho music.

Imitating a cool, South African "house" music move, I opened my hands towards the sky, towards the ground, towards the sky, towards the ground, like a god creating things. The family's fat grandma did this same move, though she barely extended her arms.

I danced with the beautifully chubby and impossibly happy mother of the family. A teacher, she'd earlier implored me to write a song that could motivate Basotho women to attend school. We came up with, "Empower yourselves ... You can help us ... Help us live better ... Study, study, go to school!"

The progressive-thinking "ntate" (father) of the family joined right hands with tiny Bobo, and they kept stepping towards then away from one another. After this, tiny Bobo took over the dance floor.

She balanced her frail body on her toes and rapidly shook her knees back-and-forth. She raised her forearms and bent her head to shoulder level; she kept passing her right forearm below her face two times, then passing it just above and behind her head. What was she doing!? Mike explained she was doing the "panther" - she was licking her paw and washing her head with it.

Man, that Bobo could dance!

Mike's and Bobo's village of Katse lied at only about a mile above sea-level.

Generous Mike baked me some curry-flavored bread to eat with my peanut butter. And the next day, I set off for the high mountains.

I hitchhiked on one of Lesotho's many dirt roads. Green mountains poured up from the road like piles of sugar. On the great mountains, in places, grazing horses appeared tiny. Homes infrequently appeared beside the road, and it seemed that they were covered by so many mountains as if to be completely isolated from humanity. The stone huts here were shorter than usual, possibly to keep the warmth in.

Because there were so few cars on this road, I didn't reach my destination. I had to sleep out here at 9900 ft. elevation, with no cardboard beneath my tent to protect me from the cold mountain ground.

The night was so dark and quiet that even the stars had a tough time appearing. Ice appeared on my tent by ten p.m. I didn't sleep much. By morning, there was enough frost on my tent to form a snowball. But, there was no one around to throw it at.

I reached Letseng (elevation 3150 m., or 10,395 ft.) that morning. There was nothing here but a diamond mine.

Large dunes of diamond-less soil had been excreted from the mine and ran down the hills. A long, white "diamond pipe" stretched along the top of a hill like a snake. Modern, red-orange or yellow buildings provided housing for the mine's workers.

An English employee kindly tried to get me into the mine for a tour. That would've been cool, but security unfortunately wouldn't allow it. So, I just waited at the main gate for my horses to pick me up.

It took the horses a long time, and the weather was too warm for snowflakes to fall. So, my high mountain trek got off on the wrong foot - especially since that foot was the hoof of a very lazy horse. My horse moved so slowly I felt sorry for him. A couple times, though, I whipped his butt good and pressed his sides with my ankles, and he trotted. I bounced on the saddle. I smiled on my horse.

My guide led me through naked green mountains. We came to the canyon of the Khubelu River. The land, bluish in the dusk, sank as if reaching for the sea. It sank like a cow's vertebrae. It sank past huts, villages, and fields of corn and yellow grass which my horses wanted to eat. It sank about as much any canyon I'd ever been in, and I'd been in the Grand Canyon.

The next day, because I was too cheap to pay for the horse again, I had to climb out of that abysmal canyon with my bags. Not to brag, but I probably handled it better than my lazy horse would've.

Reaching the top of my climb, I looked around. Near me on the mountain, I saw eighteen cows, six horses, dozens of sheep, and a few shepherds. Cornfields sprawled out below. Aah, I thought. This was the extravagant living of Lesotho.

I got back to the diamond mine, which was owned by North Americans but which also benefitted the Lesotho government.

The Mohale and Katse Dams, incidentally, had been built recently by South Africa. They currently pumped free water to South Africa. But, Lesotho would claim full ownership of the dam and, of course, water in 2016.

I hitchhiked on a main road, from this cold perch in northeastern Lesotho back towards the west.

I passed through cold fog, beside frosty snow. The damp black mountains rose to the highest road pass in southern Africa (elevation 10,800 ft.). They then shattered into tiny fragments of mountain which the road zagged crazily on in search of a sane way down. It had to be crazy to be sane.

The road lowered to the north-central district of Butha-Buthe. Here, the yellow mountains ran beside the road like table-tops. Cylindrical trees bordered them. The chocolatey huts oddly had white smudges of paint on their points. Gardens of cacti tentacles guarded homes. This was a place famous for prehistoric cave paintings and dinosaur footprints. It reminded me of Bedrock, and I could even imagine Fred Flintstone yelling,

"Boot-ha Boot-he!"

I stayed with my second Peace Corps volunteer here: a girl named Juliana. She was known to the old man who showed me her house, though, as Limpho (meaning: "Gifts").

Like Mike, Juliana was enjoying her two-year stay in Lesotho. She was doing this despite the fact that only two people in her village - and these weren't members of her host family - spoke English. This early-twenties girl seemed tough. That was no doubt because she, like me, came from Michigan. Who'd need a horse to get them out of a canyon!? Not we Michiganders!

Among Juliana's duties was to educate the villagers regarding AIDS. She told me some things about it:

It was possible for an HIV-positive mother to give birth to a non-HIV-positive child.

Once people had AIDS, they received free treatment from Western donors, in the form of ARVs. A person on ARVs could live for fifteen years with AIDS.

I asked Juliana about the lesions I'd seen on people's faces, especially in the village of Katse. She explained that this usually meant the AIDS-infected people were close to dying. As Mike had done, she suggested that the rate of HIV/AIDS infection in Katse was very large, due to the transient population that the building of the dam had brought in.

Responding to my suggestion that Lesotho would be better off without Western aid, Juliana sighed. She said: yes, without Western medical aid extending the lives of AIDS patients, the infection rate would drastically diminish. She continued: "but, then you know someone who has it, and it would just break your heart (to see her die)."

This topic of conversation wasn't exactly pleasant.

But, Juliana's rondavel was much more spacious than poor Mike's. And its inside walls - or, I should say, its ONE rounded wall - was painted light-yellow. I dreamt sweet dreams.

The next day, I awoke to see this village, which was only two kilometers away from Sehlanyane National Park.

A boy from Juliana's host family led me through the village so I could get my flashlight back. I'd lent it to the old man who'd shown me "Limpho's" house the night before, so he could find his way home.

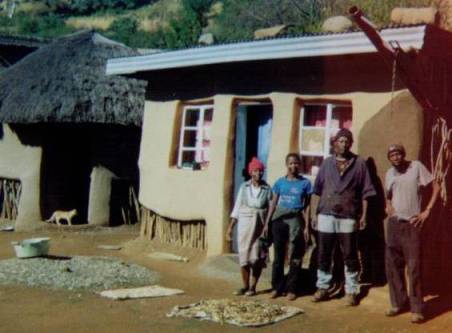

This old man and his family had about four huts and houses. Some had walls made of sticks, covered incompletely by facades of rounded orangish clay, with brilliant sky blue doors. They looked like something out of Bedrock, or a Salvadore Dali painting. They were so surreal and artistic.

- peace,

Modern Oddyseus

Thanks to Lerato; Sheus & Lejoni; Marabati + a woman; Andreas; Thabang & a woman; Kevin from Zimbabwe; Marius; someone + Ambrose; Mphou; Petjana & Nthabiseng; Karabo & Tom; and Teboho, 'Me Ninima, & 'Me Palesa for rides!

Much thanks to Nyakalo; and Limpho for places to sleep!