"South & East Africa 2011" story # 10

ADOPTED BY ORPHANS

Malealea, Lesotho

April 23, 2011

"People are starving in Lesotho,” said my friend, Bokang, while we were hanging out in his room, listening to rap music on his laptop.

The news of this statement humbled me. Starving? Really!? So, some of the people who’d asked me for money were in danger of dying from hunger? The children actively pursuing me in the countryside? The guy in the capital who looked like he was on drugs and who claimed he’d been to Phoenix? The drunks in the bars? I mean, I assumed the rural people didn’t have much money, but I figured that, due to their maize crops and livestock, they had enough food.

Now, Bokang was a funny character. His rough voice and strong, bald head made him manly. His round face and smile cutely seemed to be missing a tooth. Loveably, at age twenty-eight, he didn’t really know what to do with his life nor what he was passionate about, so he just said, “Fu*@ it,” and studied law. That seemed the easiest to him.

Sitting in his room, sad and horrified, I thought to myself: Starving!?

Then, Bokang said, “Yeah, man, we’re starving here. I’M starving! I consider myself to be among those who are starving.”

Wait a minute, Bokang! I knew that the university students received 1400 rand ($200) a month from the government. That was more than what I was living on. And I wasn’t starving! Bokang’s scary assurances lost their validity. I felt relieved.

I told Bokang (whom I sometimes called “Billy Bob” because of his love for Billy Bob Thornton) that, because he and his countrymen watched glamorous Hollywood movies and foreign soap operas, they were comparing themselves to the well-off and thus pitying themselves. They should read a Dostoyevsky or Charles Dickens novel, or a local one.

Bokang knew I’d caught him in an exaggeration. He said, “Well, Justin, if you’re asking me if I’d like to have the money that (rappers) Bright Eyez and Kanye West have, I’ll tell you … I wouldn’t mind it.

“I wouldn’t mind it.”

So, no one – to my knowledge – was dying of hunger in Lesotho these days.

But, many people were still dying prematurely. This was evident in the large number of people whom I’d met whose parents had died while they were young. Their parents had died in car accidents, they’d been shot, and – though no one had told me so – undoubtedly some of them had died of AIDS.

Among the first such people whom I met were two brothers, my age, who belonged to a family of eight siblings who had lost their parents while young. These two brothers seemed quiet: especially emotionally, where they seemed reserved and careful. They kept telling me, even though I had no worries, "Don't worry, Justin. Everything's gonna be all right."

Later on, I discovered that the Sotho word for "orphan" was "khutsana". I knew that the Sotho word for "silence" was "khutso". And I found that "khutsa" meant "to be silent, quiet".

Another time ... a girl invited me home with her, so she could teach me how to cook "papa" (mashed corn meal). She lived with: her mother, her young daughter, and the slightly older son and daughter of her deceased sister. These last two children weren't exactly orphans, as their father was still alive; but, this man refused to see or acknowledge them unless he was forced to.

After dinner, we sat around and watched South African soap operas. My friend's young daughter climbed all over her mother; she held her mother's hand and lay atop her; and she giggled at me and at everyone.

The other two children watched this with silent eyes. They seemed somberly aware that nature had been unfair to them.

I returned to my tent on the university campus, after spending one night with this family.

A cold and rainy, autumn day arrived. To my great luck, a small and quiet student - whom we'll call "Maple" - invited me to her room for tea.

The room was warmer than my tent, and I was pleased to see Maple served us hot chocolate instead of tea. I began to suspect she liked me, because 1. She was eager to do things for me. 2. She encouraged me to spend long hours alone with her in her room. 3. She was quiet, possibly indicating she wanted to do something other than talk.

I always enjoyed hanging out with people I could be quiet with - especially those who didn't watch television, like Maple.

The next day, I got an email from my friend, Zach, in America. Zach said he'd already had a date or two with a girl in which they'd observed an "Hour of Blindness", or "A Vacation from Sight", as he called it. I envied him.

When I got to Maple's room, I sat next to her and suggested we enjoy some blindness. She agreed. We counted aloud to a hundred. "Seventy-eight, seventy-nine, eighty! Eighty-one, ..." It was somehow very exciting. And, a moment after we got to a hundred, I found out that ...

Maple's lips were surprisingly plump and soft. They could firmly hold my bigger lips, yet they were so tender that they seemed to be coated in butter. The pink in Maple's lips and the brown in her face were both shades of the purple of a sunset projecting itself onto brown mountains.

That night, I would find that Maple's nipples, on her soft body, looked like the shriveled ends of burnt steaks.

She was a strong girl. She snuck me into her room so I could sleep. When guys teased her for walking with a white guy, she barked at them and threatened them, "You'd better not still be here when I get back!" She liked to listen to Christian music, such as a long Sotho song that repeated the word, "Feela!" (Only!), and she played guitar.

But, she was also full of fear. She wanted me to never sleep in my tent in the forest again, because she said bad spirits lived there. She hated darkness. Public speaking terrified her. She despised the "devil worshippers".

Ten years ago, when Maple was thirteen, her parents had died. She and her siblings then went to live with the family of their uncle. I asked if it was at this time that she became quiet. She said, no; she'd always been.

But, it was shortly after her parents' death when her faith in Christianity became solidified. Her younger brother fell sick and neared death. She prayed for his recovery.

And he recovered.

So, I had a nice girl named Maple to hang out with.

But, I still wanted adventure. And I was feeling more confident in Sotho, even though I rarely spoke it.

I took a third trip to the mountains last weekend. Not far from Lesotho's university - and at times, almost directly above it - I experienced wonderful images:

a woman wore a tribal floral dress and a bandana in her hair, in the back of a truck we rode in, as a round smooth gorge fell behind her ...

sheep covered a hilly mound ... cornfields hugged a river cutting through the land ... two oxen pulled a cart to the fields ... distant women seemed wavy and tall, because they carried bundles of sticks on their heads ...

in a village, crickets chirped loudly in the daytime ... a small girl ecstatically waved to me, then became frightened when I stepped towards her ... a crumbly, orange rondavel (hut) had a bright blue door ... a woman and I exchanged pleasantries in Sotho ... and shepherds draped their wool blankets (red & black; or blue, gray, & orange) around their shoulders and fastened them with huge safety pins.

I began to think the people living in Lesotho's mountains might've been the luckiest people on Earth.

The next day, I reached a popular tourist destination: Malealea. I began hiking in the autumn rain, and I was joined by a young and smily shepherd.

He smiled in a cuddly way and called everything "beautiful": Lesotho. Malealea. His old, gray dog. His yellow, younger dog. He said the only bad thing about Lesotho was that it had no money. He didn't have money to buy "trousers". He showed me the outfit he had on under his blanket; the pants and shirt sleeves were badly tattered.

We hiked past smoke coming out from under a ledge in the mountain, and we saw a shepherd child warming himself with a fire.

My smily companion, Orisa, told me his parents had died when he was twelve. He was now twenty and married.

He and his dogs left me to return to his sheep and wife, and I continued hiking on my own. I came to a stunningly beautiful home.

Made of rectangular rocks orange, pale, gray, and black, giving them an orangish hue, an L-shaped house and round rondavel perched near the lonely edge of a plateau. In the chilly silence, boys' clothes hung on the line. A single savannah tree dwarfed a wooden outhouse whose door was a tarp. Floppy-eared pigs and white ducks waddled around the yard.

Green mountains loomed behind the home. A black, zigzagging line of distant mountains stood as a challenge in front of it. Directly below the house was the black-and-white-striped Pitseng Gorge, where the land bulged and throbbed like salamanders in an embrace, and the narrow river looked like it would have no pathway through.

Three snotty-nosed brothers came running to me, from the cornfields beside the house. I figured the adults near the fields were probably these kids' parents. I was glad they had such a nice home.

When I returned to Roma, the university town, I knew it was probably going to be too cold and unhealthy for me to stay in my tent. But, I couldn't stay with Maple; she had a roommate.

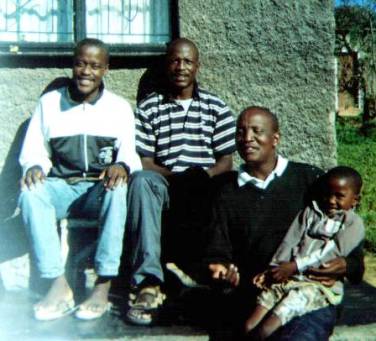

I went to the home of the aforementioned two brothers, who belonged to the family of eight siblings who'd lost their parents while young.

These eight siblings had gone on to be adopted by a local university professor, a man named Dunton from England. They'd since grown up, and many had kids of their own now. They no longer lived with Dunton, but six or seven of them still lived together.

"Don't worry, my brother. This is your home," one of them said to me when I said I'd like to live with them.

One of the family's four sisters, smily Delphina the library employee, showed me into the room I'd be sharing with her brother. She had a good heart. She said:

"Since my parents died, it taught me how to feel for other people.

"When Dunton adopted us, it really gave me power. It made me want to take care of other people.

"I come from a hard life. If Dunton wouldn't have adopted us, I don't know what would've become of me.

"Living with your brothers and sisters, it isn't easy. You know, sometimes you can have family fights. If we wouldn't have gotten along so well, I don't think Dunton could've raised us. He would have to be here, you know, and he would have to be there.

"I just thank God we get along. And now, the most important thing in my life is to help other people."

She was thankful Dunton had adopted her.

I was thankful she and her siblings had welcomed me in.

And I was thankful I still had my Mom and Dad.

peace,

Modern Oddyseus

Thanks to Leonard & Moses; Mrs. Lepoto; Shaolana & Mamarapele; Solomon, Mohale, Francis, & Justice; Mokholoko; Cheng Youqing, his relative, & Albert Senhle; Melissa; Sechaba Sekhese + 2 guys; a new semi-truck; Opa & Moja; three guys who took me in the back of their truck at 90 mph; Thabo; Ntsane & Mohala Lifeela; Abrahima, Thake, & Ernest; Vuyo; and Simon & Joseph for rides!

Much thanks to "Maple"; and Mokholoko for warm places to stay!