"South & East Africa 2011" story # 5

BLACKBERRIES

Roma, Lesotho

March 15, 2011

The many office workers and administrators of Lesotho seemed to have a stranglehold on the country. It would've taken a lot of approvals for me to begin teaching, even though a school principal wanted me to fill a vacancy he had.

The government office workers of Lesotho earned nice salaries, sent their kids to study in South Africa and Europe, flew business class or brought family members on work trips, and awarded "tenders" (contract jobs) to friends.

Other citizens faced 40 to 50% unemployment, frequently lived on less than $1 a day, and felt a sense of powerlessness. I wouldn't have minded being a shepherd, though, wandering in the mountains.

"Everyone expects to get an office job when he graduates," said a university student, Stone, of the other students.

I still stayed on-campus, although I needed to look for a job. I met the thin and good-looking Basotho (natives of Lesotho) guys. They stood tall and wore French berets; littler guys wore fishermens' hats. They greeted me with smooth, three-part handshakes. They said, "Chop! Chop!" to say good-bye.

I was mesmerized by the curvacious women. Full-bodied, jiggly girls paraded in bright pink dresses with low cuts. A caramel-skinned babe showed shiny cleavage in a tanktop, while her very short hair was braided on her cute head. A stout girl marched around in a purple-and-black striped dress, and her firm booty and hips were so wide that if I would've danced behind her I would've thought there was a sofa between us.

And I always had great conversations with the students. I advised a girl with low confidence to stop watching so many movies and act to free herself from her overprotective family. I debated religion with Christians. Once, a boy I didn't know called to me from a classroom window: "Can you compare 'autonomy' with 'accountability' for me? Do you think the two can co-exist in the public sector?"

I was surprised to see the young people were so active and inquisitive, I was surprised to see that most of them had laptop computers, and I was a bit surprised to hear they'd all been educated in English - not Sotho - since high school. I hoped these hopeful students would be able to do something wonderful after graduation, and not be restricted by the administrative "wall" ...

About a week ago, I came up with a new and brilliant idea to make money.

I would travel around Lesotho. I would visit schools! I would show the students pictures from my travels (if the schools had computers and electricity), and I'd talk to them about achieving their dreams. In exchange for my motivational educational inspirational presentationals, I'd ask for: $3.50, some food, and a place to stay the night. How could the schools refuse!?

I left my tent on-campus and began to execute my plan. I ventured off-campus and through the sunken basin of the Roma valley. Oranged yellow cliffs stepped upwards like gumdrops, in all directions. Tall blond grass swayed nearer to me and made it difficult to see more than a few buildings at once. One of those buildings was an elementary school. Made of large and crudely cut sandstone bricks, the orange school and its green window frames fit into the scenery nicely.

A week before this, I'd walked past this school. A boy in fifth grade, wearing a long-sleeved khaki school uniform that made him look like a zoo-keeper, came up to me. His name was Kelane. (Kel-ah-nee.) I liked his aggressiveness. With his friendly bald head, he asked if I wouldn't come to teach his class one day. I said, "Sure, kid."

Of course, I wasn't sure that I would. But, how could I tell Kelane that? I needed to look for a job, not volunteer to teach fifth-graders.

On the day of the execution of my brilliant plan, I went to Kelane's school. But, the principal wasn't around.

I continued on. The principal of another school gave me some crappy beans for lunch and told me to call back on Monday.

The principal of an all-girls' high school was away, attending to funeral arrangements for a student. (In this land of 23.2% adult AIDS/HIV infection, death seemed to strike frequently.) An old, female teacher sat at the principal's desk.

She suggested the school could in no way get funding for me, not even $3.50, because it would have to be approved by the same "educational secretaryblah blah blah" who'd turned down another principal's request to hire me permanently. I had met this old, female teacher before and admired her wisdom. But, on this day, I scolded her for complying with administrators in far-away offices. Calmly, she said:

"As for me, I'm done taking risks. I'll be retiring soon. I'll leave that to the younger teachers. I took risks twice: in 1990 and 1995. It was in '95 when it hurt me the most. I lost six months' salary then.

"... But, the principal will be back tomorrow. You can talk to her then."

Oh, no.

I couldn't keep returning to schools or calling them, if I was asking only $3.50 a day! My brilliant plan was a flop. I felt pain and frustration, as I walked home through the hot valley.

As if to raise my spirits, two girls from Kelane's elementary school appeared to walk with me. They wore the fresh-green sweaters and skirts that were the girls' uniforms. They had black ponytails or shaven heads, they made conversation, and I felt better.

A running boy came up beside us, and I recognized Kelane. "Hey!" I was happy to see him.

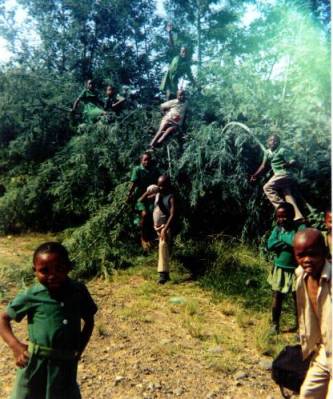

We came to some boys and girls of their school who were climbing off the ground into some bushes. I took a picture of Kelane and the two girls and the kids in the bushes, and they were happy. They made me promise to take the photo to their school once I got it developed. "OK." I promised. But, I knew I'd probably break this promise.

Suddenly, we were met by four women walking in our opposite direction. "One rand!" they said. They carried buckets full of blackberries. I guessed they were selling delicious blackberry juice. I pulled out two rand ($0.28 US): a cup for me, and a cup for my little friends.

The women began scooping blackberries. Dozens of schoolchildren materialized. They surrounded us like magnets, silent and awe-stricken. It upset me that they crowded around for such an unspectacular event. It would turn out that the women weren't making juice; they just handed me a plastic bag containing tons of blackberries. Okay; great.

I put one inside my mouth as the kids watched me. It tasted syrupy, moist, dark-violet heaven. The kids seemed surprised when I lowered the bag to share. I envisioned a great walk through the valley with friends, sharing a bag of blackberries.

But, I would only ever get one more. As soon as the surprise wore off, a kid grabbed a blackberry. The next kid grabbed two. The next kid grabbed five. The next hand grabbed a fistful. Before I could do anything about it, the tiny, greedy hands had filled themselves and pulled down on the bag until it broke. My knee and toes became stained with purple.

My earlier pain sharply returned. Furious, I looked in the direction of the greediest hand. I might've even yelled at the kid I'd see.

But, I saw Kelane.

A chorus of disappointed murmurs rose from the women and the innocent children. The guilty children were silent. I walked, angrily and silently, through the crowd and on towards the university. My brilliant idea to share the blackberries had been a flop. Maybe I just didn't understand kids.

Two girls eventually caught up to me. They looked concerned. They asked, "Is everything all right?"

Still saddened, I said, "Yeah. It's all right." But, really, it wasn't. At least, I didn't think it was.

- peace,

Modern Oddyseus

Thanks to Botata & his lovely wife; and Gravel & Mafukeng Lefoto for rides!

Much thanks to Tlali, Mantoetsi, Reana, Malepantsi, Mike, & Sefora for the place to sleep!