"Rest of the World 2013-14" story # 27

A VISIT TO THE MOSQUE

Sminja, Tunisia

February 7, 2014

"The prayer in congregation is twenty-seven times superior to the prayer offered by person alone." - the prophet Mohammed

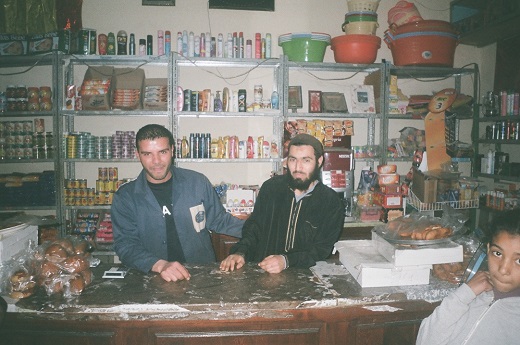

Sali the Islamic Shopkeeper wanted me to go to the mosque with him. He himself went five times a day.

He said I could go and just watch. The "imam" - the mosque's spiritual leader, who led prayers and gave Friday afternoon speeches - spoke English and could answer my questions about Islam.

I agreed to go. A shaven-headed guy named Hossein, who liked to change into a long, light-weight gown when going to the mosque, let me know I'd have to pray at the mosque. He smiled his handsome smile.

-- Pray with us! Pray with us! Pray with us! --

Aaaah. No!!! Anything but that!

"Ma-neeselli-sh," I said. (I don't pray.)

They said I could go and just watch.

But, I couldn't enter the mosque.

In Tunisia as in Morocco, it was forbidden for non-believers to enter mosques. But, I'd entered several mosques in Turkey, where the rules were different.

Mosques were peaceful, beautiful places. Large and open. The floors were soft and carpeted, sometimes covered in rugs. Bright colors in simple patterns decorated the walls. Pillars stood for independent prayer-givers to stand behind. In most mosques, a single chandelier hung in the center. Though Islam's theology was like that of Christianity or Judaism, its mosques with their bright colors and peace reminded me of Buddhist or Taoist temples.

Sali and I arrived at the mosque at just after sunset. It was time for the day's fourth prayer, the Maghrib prayer. A light rain fell. Thirty-five men arrived, washed their heads and feet with water, greeted me outside the mosque, and took off their shoes once more before entering the mosque.

Inside, they lined up in rows. The men, some of whom wore gowns, listened to the imam in front of them and followed his movements. Praying, they stood, sat on their butts, and bowed with their foreheads and hands flat on the ground. An old man sat on a stool while the others bowed. They relaxed at each position; their movements were calm and meditative. Of course, their prophet had been a calm man.

Mohammed said:

"whenever you come for the prayer, you should come with calmness"

"And whoever remains patient, Allah will make him patient. Nobody can be given a blessing better and greater than patience."

The "Muslims" (a name meaning: Allah's Slaves) finished their prayer and exited the mosque. Sali and the imam took me to a school classroom that was connected to the mosque. On the board were written the wavy, loopy letters of the Arabic alphabet I so enjoyed writing in. Ten more of the praying townspeople joined us in this room.

I was surrounded. Stubbly black beards overflowed from the faces and chins of these golden brown Arabs. Many wore light, cotton skull-caps. Some wore white aprons over their brown robes, or wore the hoods of their robes over their skull-caps. They looked at me with the big brown eyes of friendly bears.

Mejjed the Imam began telling me about Islam in English. He said that between two and four "Rakat" were performed in each of the five daily prayers. In the Maghrib prayer, three were performed. Before every Rakat, Muslims recited the "Fatiha" - the opening page of the Koran. Mejjed didn't say what a Rakat was, but I guessed it was a prayer that involved standing, sitting, bowing, and reciting Koranic verses of the prayer leader's choosing.

Thirty-five-year-old Mejjed asked if I had any questions about Islam. I began by asking why he and other religious Muslims had beards. He said all the prophets had had beards. Mohammed. Jesus. Joseph. Abraham. Moses. Etc.

I asked, Why did many Muslims insist their women should cover themselves? I recalled nothing from my reading of the Koran that commanded this, and I'd found evidence suggesting only three "Hadiths" discussed the subject. This custom made married women invisible, insignificant, helpless; and it robbed young men of the joys of having girlfriends and female friends.

The only people who seemed empowered by this custom were young women, who showed confidence in their head-scarves that said, "I don't need the attention of any man who's not going to be my husband."

Mejjed mentioned two quotes from the Koran that said women should cover themselves. His "Assistant Imam" played these quotes for me, on a microphone that translated the Koran into many languages including my own. The first quote said women should cover themselves so they wouldn't be abused. The second quote was Allah saying Mohammed's wives and daughters "and the women of the believers" should cover their heads, arms, and feet.

Mejjed said, "We must protect our wives, mothers, daughters, and sisters." If I were the women, I'd feel like I was being protected by being put in a cage.

Mejjed went on to say that the Koran was a piece of literature so amazing that no writer could equal it. He said there were mysteries hidden within the Koran, thousands of mysteries.

By this time, there were only about six bearded Muslims in the room. I felt comfortable enough with Sali, Mejjed, and the other young men who couldn't understand me, to begin my criticisms of Islam.

I asked Mejjed if he read much. Because if he, like many Muslims, never read non-Islamic literature and rarely wrote, it was understandable why he would've considered the Koran to be a great piece of literature.

To my surprise, Mejjed the Imam said he'd studied law at university. He'd read many writers, including philosophers Plato, Hobbes, and Nietsche. He found more truth in the Koran.

Personally, I considered the Koran to be poorly written. It lacked imagery and color, the things that made the fiction of Jorge Amado, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and my father Kevin Breen so beautiful. And it was repetitive, using six hundred pages to say what it could've said in much less.

Mejjed explained why the Koran was repetitive. "Some people can read something once and understand it. Other people need to read the same thing many times."

The mysteries of the Koran?

Muslims with their book reminded me of religious Jews with their Torah. Jews had even assigned numbers to the letters of their alphabet - 1, 2, ... 9; 10, 20, ... 90; 100, 200, 300, 400 - and they counted up these numbers to give each word in the Torah a spiritual value that was supposed to be meaningful. It was an alluring idea ... but, kind of insane.

Lost people looking for guidance, in every word.

Of course, if one were to compare Islam to the nihilism of Nietsche, one would find the Koran to be meaningful. My atheist boss in Turkey, Serhat, was a nihilist. He envied people who believed in God. He said they were happier than him.

Mejjed said, Muslims were happy. I looked at the smiling, bearded face of the assistant imam. Sali - who wasn't the smartest knife in the box - was happy. Mejjed's rounded teeth smiled from within his beard. He said, when a Muslim touched his nose and forehead to the ground while bowing, his stress was released to the ground. Indeed, these people who prayed together seemed happier than the average Tunisian.

I liked committed religious people more than I liked money-lovers.

But, I believed there were other options.

I told Mejjed, one thing I'd learned as I aged and progressed was that "acceptance" should be our aim. It was not only key to our treating others better, but also key to our own serenity. Openness and acceptance.

Allah was firmness. Allah was going to divide us into the good and the bad, to punish us for following our own nature. I didn't believe in punishment.

Mejjed arrived at the point of our talk where he wanted to ask me a question.

"Do you like Islam?"

-- Believe in our god! Believe in our god! Believe in our god! --

I said, Muslims were good people. They were generous. They were mostly very accepting.

But, my answer was, "No", to the religion.

The Koran was boring. Prayer was boring. It was boring to live in a land where it wasn't accepted for women to be free.

It was a mistake for us to believe we owed gratitude or were in debt for the good things that came to us freely. The religious convictions of a nation had their psychological impact on even the nation's unreligious. We should never have to pay for the things that nature provided.

Mejjed's and my conversation was interrupted, as the call to prayer sounded for the evening 'Isha prayer.

The prophet Mohammed had disliked sleeping before or talking after this last of the daily prayers.

The faithful Muslims of Sminja, Tunisia performed their four-Rakat prayer. I looked on. And then, I opened my umbrella as Sali and I and a guy named Kassem walked home together.

We passed a cafe where only men went.

Kassem, with his beard-less young face and skull-cap, asked me:

"Are you a Muslim?"

-- Give up your freedom! Give up your personality! Give up your brain. And think the way we tell you to think! --

No??? I wasn't a Muslim?

Surely, I had to be something. Was I a Christian? A Jew?

"No! No! No!" Anyways ... weren't they all the same thing?

The way I saw it was this ...

Millenia ago, the Jews began believing in a single god and a new religion. This religion excluded non-Jews. This God loved the Jews especially. A book was written. Other people heard about this religion, saw this book, and were upset that a God they'd never thought about and who was better than their gods didn't love them. The Jews, who believed they were special even in the eyes of God, developed into an ambitious and successful people.

They were so successful, in fact, that billions of people whom their religion had excluded would come to copy their religion and copy the stories in their book, and worship their God - with a few modifications. Christians and Muslims were like kids on the playground who'd been excluded from a game; they went and made up their own game, which was just a copy of the mean kids' game, with the slight modification that they were now included.

Or at least, that was the way I saw it.

And there were other differences between the religions.

That evening in Sali's house, my bearded friend told me there'd be no music at his wedding. He claimed it was "hram" (forbidden by Islam).

Hey. I liked music!

The following evening, I returned to my routine of having dinner at my friend Monsoor's house. At one point, he and his adult son and I listened to music and danced.

We were happy, too.

The Modern Oddyseus.

Thanks to Mahjoom; and Mortada for rides, while I didn't have my donkey!