"Western Africa 2012" story # 10

IN THE LAND OF BERBERS

Lakes Tizlit and Isly, Morocco

June 13, 2012

Hamid and Hadeejah's wedding ceremony had been hosted by the bride's family.

The following day, the groom's family would invite many guests over for dinner. The bride and groom would then go into a room together. And then they'd have sex.

"Did I really want to enter and claim possession of these beautiful creatures?" - a male J.M. Coetzee character

I wasn't disappointed that I hadn't been invited to this dinner. I was having enough difficulty just coping with the heavy heat of this part of Morocco! I caught up on my sleep. And in the morning, I headed for the cooler High Atlas Mountains.

My amibitions for this time were three: 1. Improve my Arabic. 2. Move south towards Mauritania, Senegal, and Guinea-Bissau (the next country I hoped to spend three months in). 3. Do some writing.

I camped beside Lake Tizlit, at 2321 m. (7659 ft.) above sea-level. It was surrounded by a few green poplar trees shaking in the wind, uneven bumpy mountain ranges, and one mountain that was a perfect cone. My only ambition which I'd accomplish was my ambition to write. I'd also take in a bit of the local culture ...

I finished my writing as dusk was falling, and I took off to walk the eight kilometers to Lake Isly. Legend had it that Isly and Tizlit were the names of lovers whose rivalling clans forbid them from marrying, so they cried these two lakes. It was true that, in August or September, dozens of couples married every year in a festival held nearby.

What a romantic place.

An empty, desolate, eerie, unwanted, abandoned land flowed between the two lakes. It bulged around me and was occasionally decorated with fields of yellow flowers. Distant mountain ranges wore dark shadows. Darkness fell.

Dogs barked. Sheep "baa"ed. Shepherds yelled at their flocks. Berbers, the indigenous people of Morocco who pre-dated the Arabs, lived here.

I came to a small community of low-topped, square, glowing gray houses. A silver bike-light raced out to meet me. "Bois the?" a twenty-year-old man asked me. (Drink tea?) Yes, I said.

He took me around the community to his home. We entered a building with two or three rooms, small and empty, like the insides of boxes. I somehow fit through the kitchen door with my backpack.

An old man, Hssein, sat on the floor. He had a long and bulbous nose, long ears that stayed near his head, a sharp protruding chin with bristles of dark hair sticking off it, wrinkles carved into his sun-browned forehead, and a white sheet wrapped around his head. His twenty-year-old son's head had the same shape, with a navy cloth tied around it.

The little, sixty-year-old mother had pink-and-green clothes tied around her haphazardly, a rather bare head, and few teeth. Her softly-voiced words squibbled together like a sped-up tape. She stood and cooked over a gas tank. In this small dark kitchen, I thought, they lived like mice.

I felt warm and toasty and sleepy here. Thick blankets were laid out below us. The earthy wall cracked behind us.

None of the family could speak French well. The old man kept trying to talk to me and chuckling cutely. He poured us sugary tea. Two cats cried for food, and I was told the Berber word for cat was "moose".

The mother served us a hot potatoes-and-carrots-and-chicken "tagine". I was invited to spend the night. The family would be sheering its sheep the next day.

I thought about staying. But, then, a professional sheep-shearer arrived. Hssein's oldest son arrived. And then three more men entered this tiny kitchen. One man seemed gigantic, with his shepherd's staff, his flowing blue robe, and his gigantic wrapped-up head. He was like a Berber God.

My bags and I felt a bit cornered, so we went on our way.

... out into a bright naked world illuminated by full moon. The distant mountains glowed green. I navigated my way through a metropolis of resting sheep. Where did they find food? I thought. Hssein's oldest son had told me he sometimes had to lead his sheep far in search of grass.

I pitched my tent upon a dry ravine of sand. I meditated.

Silence.

Clouds filled the sky. The many square clouds looked touchable, reachable, as if I could climb on them and live on their undersides, like Earth. Up was down. Gravity was opposite, and there was no sky between us.

The outer-space blue pool known as Isly filled a giant crater basin. Nothing surrounded it but dark moon soil. Swimming in it, I found the water to be infinitely clear, an icy blue. I felt as pure and free as a baby bird. Though cold, the wavy lake was a swimmer's dream.

Three young women approached the lake on horse-back.

Black fabric covered one. Only her cute, pointy-nosed face and sharp teeth were visible. In a curious and loving voice, she asked my name: "Comment rapelle on?" She asked if I was married.

Her name was Houria. I wanted to stay with her all day beside the lake and put my arm around her. But, I'd already told the other tourists visiting the lake - an Austrian couple and an Italian couple - I'd travel south with them.

The Italians gave Houria a pen. "Un cadeau," they said. (A gift.) She said, "Un cadeau? C'est un petite cadeau. Donnez-moi un grand cadeau. Je t'aime." (A gift? It's a small gift. Give me a big gift. I'll love you.)

As we travelers were leaving, one of Houria's friends led a mule down to the lake. Houria joked that it was "un cadeau" for me.

I rode with the Austrians, retired Petr and Ushi, in what seemed to be a Hummer. The white-haired Italians, Pierrino and Oriella, drove a white camper-van that rose upon wheels as tall as the Hummer. The sides of the camper-van were decorated with maps of the countries the Italians had driven around: Libya, Algeria, Mali, Mauritania, etc. These guys were my heroes of Saharan travel.

We'd need the big vehicles this day. We would drive twenty-five miles (42 km) on a road made of rocks, wedged in-between the mountains. That short road would take us four hours to travel. Maybe I would've gone faster on Houria's mule?

We began our journey on a better road. In villages, kids waved to us, with faces softly oranged by the sun (with red circular cheeks) and well-wishing smiles and long eyelashes as wet as the land was dry.

Outside the villages, the high land abruptly dropped - like a man standing on a trap door - into a deep cirque. In places, the cirque stepped downward with ten-foot cliffs as steps; but the land was crooked, so it looked like an audience of Workers' Party ralliers standing on bleachers and thrusting their fists into the air.

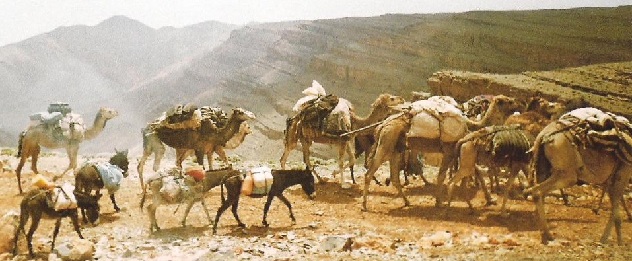

To make this scene even more impressive, men with wrapped-up heads led camels across the road in front of us. Women wrapped in blue and red, with children clutching them, rode on mules and accompanied the men. I exclaimed, "That's amazing!"

We reached the slow, rocky road. No villages were to be seen. People occasionally appeared, running down the steep mountains towards our vehicles. Often, their objective was to beg from us. One woman called for "khobz!" - a rare Arabic word which I understood. (Bread!) She also called for the local currency, "dirham!"

I asked Ushi the Austrian what she gave to the locals: the locals who begged, and the locals who invited her in for meals. She answered, "Never money."

Two ten-year-old girls begged from us. Their blood-red fish lips and wide open eyes were adorable, though serious and desperate. They were obviously twins. They pawed at us through the windows. Ushi gave them candy, a shirt, and a towel. They wanted more. "Leemon!" Ushi gave them a bag of lemons.

They returned up the mountain they'd run down. Ushi said, "Aack, they're so dirty! There's no water for them to bathe in around here. And they all have the dark-orange henna tattoos covering their hands."

She also felt the children of Berber shepherds had unfortunate lives. I, however, saw a harmonious beauty in their simple homes and their intimate relationship with the land. I figured they'd probably been better off before they'd grown accustomed to the tourists' gifts. But, perhaps I was wrong?

We reached our destination, the Dades Gorge. It was as if the land here was a big moist spongecake, and a giant had stuck his finger in from above and wiggled a deep and winding path through.

Unfortunately, as I drew closer to Mauritania and Guinea-Bissau than I'd ever been before, I learned I'd need a pre-obtained visa to enter Mauritania. How was I going to solve this problem?

And was I ever going to learn Arabic?

until next time,

the Modern Oddyseus

Thanks to Khamal & Mustafa; Majid; Bushayim, Hamsa, Aziz, & Siyam; Petr & Ushi; Joe, Joe, & Jim; and Said the taxi-driver + the guy who'd probably paid for me, for rides!