"China 2010" story # 18

V (TIBET)

Jonglulan, Qinghai Province

August 12, 2010

I got diarrhea at some point, in Gansu Province.

Then, I went west to Qinghai Province. Qinghai is China's third-westernmost province, and the westernmost one I will visit. To the northwest is Xinjiang ("New Border") Province, and from there you can get to Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, or Russia. To the southwest is Xizang Province (commonly thought of as Tibet), which borders India, Nepal, and Bhutan.

In fact, most of Qinghai Province lies on the Tibetan Plateau and - to my pleasant surprise - is populated by Tibetans. China probably split the Tibetans up on purpose, in order to undermine their national spirit.

Slowed down by my stomach woes, I spent two nights in the province's capital. The small city was more Muslim than Tibetan: burly men wore white, head-hugging caps and uncompetitive smiles; women hid their heads in black cloth resembling executioners' masks; and lemon-lime-vanilla mosques called the neighborhood to them for prayer. The city was 2200 meters above sea-level. I worried that my body was weak due to altitude sickness, and that I wouldn't be able to explore the Tibetan Plateau. But ... lured by a thirst for cold summer air, and the desire to say, "Yakkity-yak, no talk back," and actually mean it, I pressed forward, upward, onward.

At 3000 meters, or 10,000 feet, I camped beside "Qing Hai" (Clear-blue Sea) - a huge, salty lake that gives the province its name. Grassland surrounded the lake, except for sand dune mountains that stretched a ways into it. By day, I could climb the dunes and chase my tennis ball down them. At night, the big sky was peppered white by the Milky Way, and I felt like a part of it.

Hitchhiking south, I got picked up by a man with sun-blackened skin and a thin neck and small head and big nose and swirly ponytail. Like most of the people I'd come across in this part of Tibet, he didn't speak Chinese.

Next to me in the car was a girl named Dim, who'd just finished studying Tibetan culture at a university in Beijing. She lamented that she didn't look Tibetan, because the low-altitude sun in Beijing had left her skin light. I wondered why she'd gone to Beijing to study Tibetan culture. She said she'd be doing her post-graduate in Qinghai.

She said the Tibetan culture is strongest now in Qinghai Province. This hadn't been the case before. Maybe China is trying hardest to repress the Tibetans in "Xizang", supposedly their autonomous region?

I asked if Tibetans prefer to be a part of China or to be free, and she said they want freedom. She said many Chinese people are moving to Tibet. She frowned. She said many Tibetan children learn Chinese culture and have forgotten their own.

For lunch, we ate a Tibetan stew: chunks of lamb, green pepper, thick potato ovals, and thin tortilla bread, made soggy by the meaty stew. She lamented she couldn't put together a Tibetan dance show for me.

South of Dim's town, the tree-less and mostly flat plateau became full of yaks. These shaggy cows came in black or white or both. From a distance, moving across the grass, with unseen legs, they looked like an army of cow ghosts - or, like a bunch of people wearing those two-person cow costumes. Up close, the white heads and hollow eyes and horns looked at me like skeletons.

That night, I was going to camp near a lake, but I worried I'd be afraid of wolves in the pitch-dark. The white, family tents of yak-herders weren't far away. Few people in this area were urban dwellers; many Tibetan men had long, wavy, dark hair, wore Wild West leather hats and vests, and had cooked, dark skin. One such guy drove me on his motorcycle to the family tents, after I drew and acted out a wolf biting me. I hope he didn't think I was afraid of the prairie dogs.

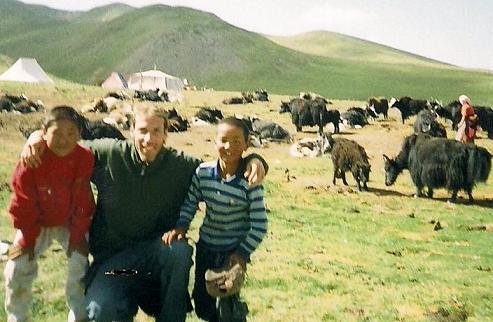

Whole families of yak-herders welcomed me, and helped me set up my tent next to theirs. A few people could speak Chinese. Ten-year-old boys and girls fought to see my pictures. I played my round flute, and one boy clapped along. I asked if they danced, "Tiaowu?" and everyone laughed. Dark night was falling, on 3800-meter or 4800-meter-high land.

The inside of the yak-herder's tent - like most Tibetan culture - was colorful. Pink flowers on red and yellow cloth decorated the ceiling; pictures of the Dalai Lama and colorful idols decorated one wall; I tried to sit on stacked-up blankets, and everyone laughed and told me to sit on a mat or the grass. The yak-herder's wife scooped dry yak poop into a stove in the middle of the tent, and she offered me twisty bread and filling yak-milk tea.

We were all men, except for her. I asked why no "nu" (women) were eating with us. Someone said, "Tamen chi cao!" (They eat grass!) And I realized they must've thought I was asking about the "niu" (cows). Ha ha!

Before going to bed, we ate soup: noodles and cucumber and yak meat, which was dry like cow tongue. The night was pretty cold. Yaks kept grunting near my tent, and they sounded like old cars trying to start.

In the morning, the wife and daughter milked the yaks.

It's the Tibetan women who wear the most beautiful, traditional clothes. Their hair usually hangs off their heads in long braids. They've aqua stones on their necklaces, strings dangling off their bracelets, colorful stones on their rings, hemp sashes across their shoulders, and prayer beads clutched between their fingers.

The yak-herder's nine-year-old daughter stood as her mom combed her thick hair and put it in a ponytail. Her silent eyes stood on-guard, and her reddened cheeks showed fire. Her shirt was purple with orange sleeves; she wore a traditional, bright-green skirt to her feet; she tied a purple-pink-and-white-striped apron around her waist to milk the yaks; two pink flags hung off the back of her dress; and she put on a mask to protect her mouth from wind-burn. It was unreal to look out my tent, where I was writing, and see this little girl trying to pull a stubborn yak by its horns.

For breakfast, the wife gave me more yak-milk tea. This time, it had butter in it, as well as a sweet powder that thickened it and which tasted like crushed cookies.

The next morning, I breakfasted on a thick soup that was made thick by the ground meat that was in it. Though the Tibetan food was very solid, my poop still wasn't. Otherwise, I felt great.

Four hundred kilometers away from my yak-herding friends, at 4400 meters (14,320 feet), I was near Yu Shu. Months earlier, this small city had suffered a devastating earthquake.

Twenty-five-year-old "V", a gentle student studying English and Tibetan so he can tell people about the Tibetans' situation, sat next to me at breakfast. According to him:

Ten to thirty thousand people had died in the earthquake, though the news reported only 3000 fatalities. China hadn't done a good job of relieving the disaster. Following the earthquake, Tibetans who had homes fall in good, central locations were moved far away, and the Chinese took those good locations. Yu Shu is all Tibetan, except for the government.

Near to Yu Shu, there was a sacred mountain that had had a lot of gold in it. The Tibetans hadn't wanted it, saying it belonged to the Earth. The Chinese took it, and three days later the area was hit by a 7.1 earthquake.

Now, the government wants to develop nearby pastureland so they can build a railway to Yu Shu. Maybe it is this area's lack of a railway that has allowed it to maintain its identity?

Qinghai Tibetans, apparently, wear long hair and speak frankly. Tibetans in nearby Szechuan Province are good at business. And Tibetans from holy "Xizang" supposedly pray a lot.

However, the holy Potala Palace in Xizang is no longer inhabited by monks; it's full of policemen. Most of the monks had been killed in 1999, when the government labelled them, "Tibetan soldiers". Now, people must pay to enter this holy site; V thinks that's absurd.

Like many young Tibetans I've met, V had gone to India as a refugee around 1999, and he's only recently come back.

I left my bags in the colorfully-windowed house of V's mother, and caught a ride to Yu Shu. I got a bad feeling, as I watched government construction being done beneath hillside monasteries. Chinese flags flew in great number. Earthquake victims lived and did business in military-style, blue tents, bearing four Chinese characters: "Minzheng Jiuzai" (Civil Administration Disaster Rescue).

The town of Yu Shu wasn't actually very interesting. Most of the rubble had been cleaned up, and life was "business as usual", except that people sold washing machines or hot meals out of tents.

Five kilometers away from Yu Shu was a pilgrimage site. In the pilgrimage area, there were temple buildings that you could enter, to see golden Buddhas in the dark, surrounded by yellow flashing candles. But, most of the pilgrimage area was a giant heap of stones. Pilgrims had written mantras on these stones, with looping curly Tibetan script and bright colors, and then thrown them onto the heap.

Pilgrims of all ages - many of them withered, old women in traditional, black gowns - walked circles around the pilgrimage area, all walking in the same direction.

Tibetans aren't very educated - an English-speaking young man named Jampa Tenzin told me. Until recently, many used to carry long knives, and it wasn't uncommon for neighboring herdsmen to kill one another in family feuds.

But, the pilgrims of today were very cooperative. Men and women formed human conveyor belts, standing on ladders and on the heaps, passing "mani" (mantra stone) after mani to the top. Jampa Tenzin said, there would be more pilgrims than usual this year.

"Tashi Delek" (a Tibetan greeting),

Justin

Thanks to Jong Tao + 3 guys + 1 girl; Yao Ting & Yao Shui & a bus full of family; Sanjojia & Jiabao; Jiaxi & another driver; Wang something & Ding Weihai; Li Shuairong + 2 other policemen + 2 girls; Li Shulin; Sonan & his family; and a black pilgrim for free rides!

Much thanks to Cairadoji & the herdsmen; and V & his mom for hosting me!