"Siberia 2007" story # 24

BARE-TOP MOUNTAIN

Lake Kolxoznoe, Resp. Altai, Russia

July 28, 2007

The first place I went to in the Altai Mountains wasn't as pretty as the pictures which Alyona, the squiggly-eyed Bashkirk painter, drew of it.

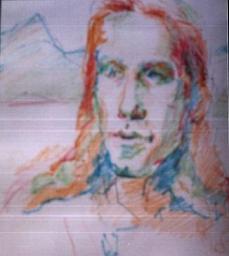

Handicapped by the fantastic, rather than natural, colors of her colored-pencil set, she scribbled blotches on her paper that resembled the different shadows caught by objects. She drew the giant lake we camped on, with light-green grass and noble red-and-orange trees in front of it. She drew my face with my hair down, in light-green and blue and orange, and I looked like a strong and proud, fantastic lion. In black-and-white, she drew a bay sipping into land - a dark but beautiful picture that could put a child to sleep.

Alyona says you can draw the soul of a person. You can also photograph a person's soul, she said, but it's difficult to do. In another picture she'd drawn, my flat face looked reserved and distant.

Perhaps I am a bit of a loner - especially when compared to the group-minded Russians who don't mind sleeping three to my tent.

(The last time we'd slept three to my tent, in America, poor hillarious Joy Nalywaiko - my guest whom I was try to show a good time - lay scrunched in the middle all night without sleeping, until a passing-by raccoon managed to headbutt her at four a.m. Poor Joy. We gave up and drove home.)

Okay; back to the Altai Mountains.

Alyona and a friend of hers left. I proceeded to continue (continued to proceed) what shall become a full summer of broken-shoed homelessness. The weather is hot and seldom rainy; the ticks have disappeared (but they're sneaky! so I still check myself regularly); and the summer camps are state-owned and not hiring. Being homeless ain't always easy. But, it means I'm free to explore.

The northern Altai Mountains are small and forested. They blow like waves across land flat like a record album. In the valleys, wooden villages that are adorably messy remind one of frontier towns in the old American West. Dry-wood boards seem to haphazardly form the attractive, sturdy shacks the locals live in. Some houses are cozy neighbors, and others are solitary outliers.

The southern Altai Mountains seem ancient, untouched by man's existence. From a main road, you can see the mountains' southern sides, which are tree-less. The tall steep mountains seem to have an understanding with the Chuy's flat valley, also tree-less and broad and a sunny spongy-moss green, because they come together abruptly but gracefully. Some bare cliffs has grass-stain splotches on them. The most-gorgeous hump-shaped mountain wore square, breathably-yellow boulders that sunk into its skin all over; it resembled comic-book-character, The Thing.

Fifty-year-old tourists Seriozna, Vera, and Olga drove me along the "Chuyskyy Trakt" (the romantic road through the Altai). Healthy Seriozna (a male) told me Russians love to sing, even if they have terrible voices. He said children used to play hockey for free under communism, but now it's expensive and therefore rarely played. (Perhaps this and similar things are the causes of young Russians being bored and smoking from age ten.) And he said Genghis Khan's army had come through the Chuy Valley centuries ago.

Vera, who owns Turkish-clothing stores, handed me two-thousand rubles ($80) after we spent twenty-four hours together. I hadn't wanted the money; but it's gonna come in handy! I can develop photo's and buy clothes for the upcoming school semester. You normally can't do those things when you've only worked 140 hours all year. (I don't want to overwork myself.)

I spent that next night on a mountain. I would later name that mountain.

If you want to get to this mountain: turn L from the south-bound Chuyskyy Trakt at Aktash, proceed (or continue) twenty kilometers through compressing canyon walls on a dirt road to Ust-Ulagan, turn L on a virtually empty dirt road leading to two wide midnight-blue lakes, and turn L again not far after "Mertvaya Ozera" (Dead Lake), push open the barrier blocking this dirt road, go to noise-less black Lake Kolxoznoe where Altaian "Elik" works providing tourists with fishing vacations, cross the lake in Elik's boat, and then for two-and-a-half hours walk through rumoured "bear territory" forest to a cirque (an opening in the mountains, surrounded on three sides by mountain) and climb.

A broad mountain plateau awaits. I named this mountain "Golyy-Verx Gora", Bare-Top Mountain, because Elik couldn't think of a name for it. The plateau is grassy but plant-less.

When I reached the plateau, I dropped my bag, took off my shoes, took off all my clothes, and set off in the warm sun to explore. Hence the name: Golyy-Verx Gora.

To all directions, distant brown mountains galloped through sunlight. I stood atop a rock-pile which I dubbed Bare-Top Mountain's Highest Point (6700 ft. ?). It took an hour to reach the plateau's opposite end. There, I saw tall black mountains with arrow heads, strangled by awe-inspiring enormous snow drifts.

I returned to my clothes, set up my tent, and meditated for a few hours.

I figure, if my shoes got holes in 'em, I'll come to the mountain where I don't need them.

- Modern Oddyseus

accompanied briefly by Alyona & Simyona

Thanks to Pasha; Valdimir, Nataly, & Anton; Andrei; Vyukr; Vladimir; Valyerii; Sergei; Sonya & Zenia; Ivan; Tim; Vinyamin; Nikolai; Igor; Andrei, Vitali, & Tanya; Zenia, Marina, & Dima; Oleg; Anatoli; Oleg; Pofku; Olesa; Nikolai & Olya; Valodya; Narkis; Oleg, his Kazak wife, their Kazak daughter, & Axple; and Seriozna, Vera, & Olya for rides!

Much thanks to Antonina Alexandrovna & Simyona; Vitali; and Seriozna, Vera, & Olya for places to sleep!