"East Europe 2005-06" story # 30

CARNAVAL IN PATRA

Patra, Greece

March 11, 2006

Another thing I must mention about vows is that, according to that wise guru Gandhi, it's futile to make a vow which you would have a desire to break. I thought hard before making my vows, and that's why I think they won't be broken.

Although my vows remain in healthy status, I, myself, have been insulted.

Mrs. Bonita Harmond called to my Michigan home recently. She's a light-skinned black lady who was wearing Southern church clothes when we'd met in Mississippi, when I was a long-haired hitchhiker in 2003, and she'd taken me and her son out to lunch. She was calling my house now to check up on me. My mom told her I'm in Greece. Mrs. Bonita Harmond's willowing voice responded:

"All I know about Greece is, it's in his hair."

The worst thing is that my mom laughed too.

But, that mean ol' Mississippian was right about one thing. Greece and its people are often tough to understand. Take, for example, the Carnaval tradition held yearly in the city of Patra. Locals will tell you it's the third-biggest Carnaval in the world. A hairy-grizzly-bear guy named Kyriakos, whose name means Sunday, who works as a journalist but speaks with the conciseness of a toddling newborn goat, explained to me the phenomenom of people paying money to be in the Carnaval parade, while he was stoned:

"Just imagine it! These people can pay thirty euro's to go be in a parade, wearing costumes, where everyone can see them! I mean, they can walk down the street, for two hours, wearing some crazy costume, and the whole town can look at them! I mean, can you understand it!? Some person, who's just an everyday person, like you or me, can pay thirty euro's, and then, he gets to be in the CARNAVAL PARADE - once a year - walking down the road, and everyone can watch what he's doing!"

I still didn't understand. Why, first of all, would you have to pay to be a public performer? Secondly, why would spectators line up to watch for hours an unrehearsed parade of talent-less people walking and dancing in the same silly costumes as their friends? And thirdly, why would this whole thing be done on not only one day but two!? It sounded ridiculous, to me.

On the days leading up to Carnaval, bad Spanish or Brazilian pop music played annoyingly loudly on city speakers. And on the early afternoon of Saturday, the first day with a parade, the streets were obnoxiously mobbed with yuppy Greeks in sun-glasses and people selling things. I got out of town to go work in relative peace.

After obnoxiously selling my things (stories), I rode on a bus back to Patra, which got filled with fifteen people wearing ridiculous sailor costumes. They wore white-and-blue-striped cotton shirts, orange or red life-jackets, ridiculous blue thimble caps, and white pants or skirts with red-striped stockings. What made this more ridiculous was the fact that I knew these people. They were international students at the local university, and I'd recently begun hanging out with them.

At one point, a happy tiny Portuguese girl named Raquel asked, "Do you like our costumes?"

"No," I said.

The international students rushed to join their "omada" (group) in the parade that was about to begin. I paused amongst the five-story, white mortar, balconie'd buildings that steal the sun from Patra city. And I spectated.

Now, the huge speakers on street-corners boomed better music: modern, progressive, mellow, rocking beats that would give the paraders energy. And the parade began. It was ridiculous, just as I'd expected. But wonderfully, irresistably ridiculous. It was almost the greatest thing ever.

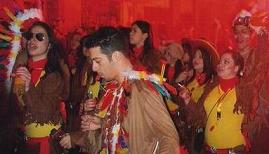

The parade was made up of over a hundred "omada"'s. Each omada had from sixty to three-thousand participants, who dressed alike and walked together. Some groups dressed as chickens (the men) and health-inspecting nurses; others as maroon-wearing traditional Japanese girls; white or pink bathroom sponges; brown-and-bright-yellow-wearing American indians; safari-goers; policewomen and convicts; and many other things. The participants were mainly between eight and thirty-eight years old. Being Greek, they had dark features; the girls often appeared to be sweet.

The paraders did nothing special, but it was great to see two-hundred-thousand people smiling for no reason other than that it was Carnaval and they were in the parade.

A common parading/dancing move was for people to spring-step with knees high, and then cheer and launch themselves forward with their arms raised. Some guys paraded with smaller males or females seated on their shoulders. Other guys locked wrists with friends and spun themselves around dizzy. Some paraders grabbed spectating children and made them dance. Other people just strolled and talked. One guy with a huge belly just ambled with a sour face and drank his beer. Generally, there was a lot of jumping and twirling and shouting, a bit of drinking, and a ton of smiling.

The wonderful parade lasted about three hours. Afterwards, the partying and dancing and silly costumes rejoiced in the streets. I found the international students and their ridiculous thimble caps, and we danced until five-thirty in the morning.

My sailor friends and the Carnaval's second parade was ready the next day at two p.m. Once again, street-vendors sold balloons, whistles, sun-glasses, big artistic wooden animals from Africa, grilled souvlaki (I was told that during Carnaval this meat may actually be "dog"), stuffed animals, and plastic caveman clubs.

But, I didn't wake up from my tent 'til it was too late. I missed most of the bigger - perhaps better - Sunday parade. This time the omadas had their own floats with them, and my sailor friends marched beside a fake boat that had been constructed for the parade. I did get to witness an omade of orange-t-shirt boys who stood on each other's shoulders to create a three-story-tall human pyramid, and the top guy led the rest of his omada and the spectators in a big cheer.

The after-party was bigger this day, too. I found myself once walking through a side-alley so dense with people that we could barely move our arms and we could only advance when everyone going our direction pushed on each other just right.

A small part of the dancing I did this day was done in Gogo's cafe/bar. The tight place hosted early-thirties girls, and guys wearing fuzzily-cartoonishly-proud orange-and-green vests and tall, yellow Mad-Hatter "skoufous" (hats). Greek cafe music is often hip and cool, but Gogo's hosted the best deejay I've ever heard.

His electronic music was loud, but soft. It was sweet. It never klunked. It was like a river through a land of fantasy. Everyone in the little bar danced. The music lifted us to the stars, and the perpetually smiling guy next to me reached out to pick them from the sky.

Later on, I found the international sailor crew. We danced once more to the early morning. A shaggy-haired Italian guy blew his whistle to the music in sync with a local guy. And this time, when I looked at Raquel in her ridiculous outfit, I wished I was wearing one.

- peace,

Modern O.

Thanks to Nikos Stamatopoulos; and Roberto for the rides!